Hello, my darklings. It’s been an embarrassingly long time since I’ve composed a new post for this blog. My other projects have managed to keep me away — but I’m back. I’ve decided to rectify this prolonged blog-neglect by posting, over the course of several weeks, excerpts taken from the lecture I gave at the Black Museum in Toronto on the topic of “Erotic Grotesque Nonsense”, a cultural phenomenon that developed in 1920s-30s Japan. I hope you enjoy, and find the posts entertaining as well as informative.

Synopsis

The interwar years in Japan were a time of rapid modernization and social change. It was also a time of economic hardship and, as the fascists rose to power, increasingly oppressive politics. During these difficult times, a popular cultural phenomena flourished. Dubbed by the Japanese media as ero-guro-nansensu, or “erotic-grotesque-nonsense”, this movement rejected the narrow standards of conventional morality insisted upon by the fascists, and instead celebrated the deviant, the bizarre and the ridiculous.

In terms of timeline, we are focussing specifically on the years 1923 to the mid-1930’s. Ero guro developed and emerged as a mass-media driven cultural phenomenon shortly after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, and faded out by the mid-1930’s due to Japan’s increasing militarism and invasion of China (and, subsequently, WWII).

Defining Ero-Guro-Nansensu

The clearest and most succinct definition I’ve come across for ero-guro is the one by offered by Jim Reichert, a professor of Modern Japanese Literature at Stanford University. Reichert describes ero-guro as:

“… a bourgeois cultural phenomenon that devoted itself to explorations of the deviant, the bizarre, and the ridiculous. […] [Such] works were produced and consumed at a historical moment when Japanese citizens were bombarded by propaganda urging them to devote themselves to such “productive” goals as nation building and mobilization. In this context, the sexually charged, unapologetically “bizarre” subject matter associated with erotic-grotesque cultural products is reconstituted as a transgressive gesture against state-endorsed notions of “constructive” morality, identity, and sexuality.”

Rather than simply a form of escapism, Reichert suggests that ero-guro may have formed (if indirectly) a radical resistance to the totalitarian political state.

Let’s break the phrase up into its three constituent elements:

- Ero (“erotic”) representing the erotic, or the pornographic. Typical motifs include sexual obsession, fetishism, and other paraphilias. Can often be represented by cross-dressing and fluid gender identities.

- Guro [hard ‘G’ GUH-ROE] (the “grotesque”). Often represented through physical deformity, also through mental instability, disguises, and the dangerous double or Dopplegänger. It is a common misconception that guro is synonymous with gore. While guro can often be gory, it is not a necessary component.

- Nansensu (NAN-SAY-SUE] (“nonsense”)

Representing fantasy, the supernatural, and the absurd. This is the element that can be often overlooked in ruminations on ero-guro — it’s darkly comedic underpinnings.

Ero guro nansensu is a wasei-eigo [ WAH-SAY AY-go ] phrase, meaning that the words are borrowed from English, made to confirm to Japanese and are given meaning as Japanese-derived English (this distinct from engrish). The phrase itself is an example of the Western-inspired modernism that came into vogue during the 1920s in Japan which, in turn, fed into the phenomenon of ero guro. By which I mean that ero guro was initially inspired by Western cultural products such as the gothic-mystery stories of Edgar Allan Poe, which was then absorbed and transformed by ero guro writers like Edogawa Rampo (whom we will discuss in a later post) into very Japanese cultural material.

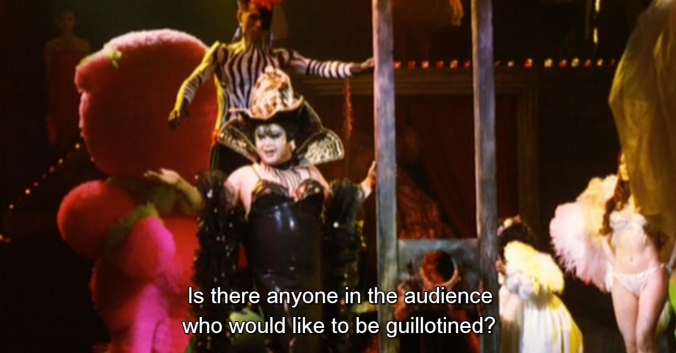

I began my lecture with a clip of the opening scene from Sion Sono’s 2005 film Strange Circus. My rationale for this was that, in it’s mere two minutes of running time, this scene so perfectly and concisely encapsulates the main themes and motifs that typify ero-guro-nansensu, or “erotic grotesque nonsense”. The scene in question is not available freely online, but below is the trailer, which should at least give you the flavour of Sono’s film.

So, what are the “erotic grotesque” elements in this scene?:

- An audience composed of ‘decadent’, cosmopolitan and stylishly-dressed youth (note the 1920’s style of clothing). These represent the original consumers of ero-guro. Note that Reichert’s definition of ero-guro indicates that this was a “…bourgeois cultural phenomenon”. This detail is key because, although ero-guro was disseminated widely through the use of print and other contemporaneous media, it remained a largely urban, middle-class phenomenon. The reason for this was simply that the more affluent Japanese citizens had the leisure time and finances to patronize the cafes, movie theatres, and dance revues that were the modern playground of ero-guro.

- The representation of fluid gender identities and sexualities (which would have been labelled ‘deviant’ in the context of the 1920’s-1930’s). Our host, Black Shadow, would embody these blurred gender boundaries.

- Heightened theatricality and performance (motif of the circus and the circus ‘freak’). It could be argued that ‘ero guro’ and the Gothic aesthetic are distant cousins to each other in terms of theatricality. Also, an element of camp can often be present.

- Violence, either actual or suggested.

- Underpinning of absurdity and humour. After all, this is erotic-grotesque-nonsense. All three of these elements are conjured in this last image, showing the moment when Black Shadow asks the audience if any of them would want to be guillotined.

Imperial Japan

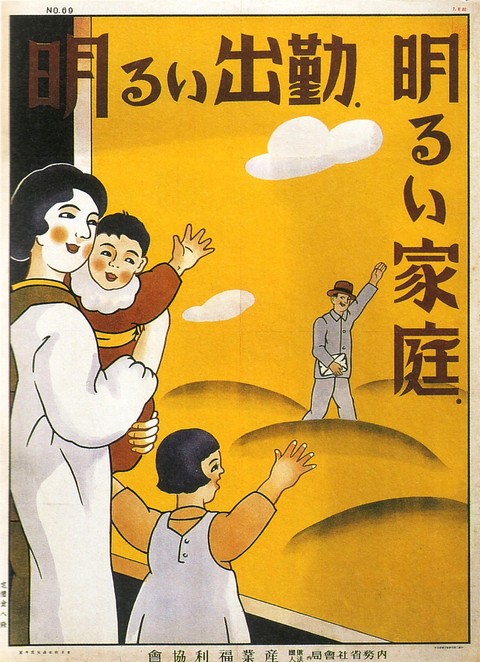

During the age of Imperial Japan, a concern for “racial health” and for Japan’s ability to fight wars, expand its empire, and claim its position as a great world power motivated a new societal power over sex by the fascists.

A propaganda poster circa 1930’s, urging Japanese women to remain in the home raising the next generation of healthy, productive Japanese citizens.

Public officials, schoolteachers, and sexologists worked together to classify individuals by sexuality and control behaviors that they marked as “deviant.” The cultural phenomenon of ero guro responded to and opposed these life-for-the-empire biopolitics of the fascists by imagining a possible alternative. Cultural critics such as Jeffrey Angles (in his essay “Seeking the Strange…”, published in Monumenta Nipponica), have interpreted the interwar fad for the erotic grotesque as “…reflecting people’s desire to escape the difficult economic circumstances and increasingly repressive political developments of the 1920s and 1930s for an alternative sphere of imaginative play.”

One of the chief sources I consulted for research on the erotic grotesque was Miriam Silverberg’s book entitled Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Modern Japanese Times. This is a densely packed academic text that examines, in great detail, the emergence of the erotic grotesque as a cultural phenomenon. Silverberg offers four major factors that she asserts contributed to erotic-grotesque nonsense:

- The changing roles of women.

- Changing attitudes towards sexuality.

- The emergence of new public spaces.

- Mass culture & modern consumerism.

Following an economic boom of WWI, Japan quickly fell into recession. This economic decline pressured women, who had hitherto remained in the household, to enter the work force. Women belonging to a higher economic/social status entered the “white-collar” work force as secretaries and other office workers. These women were dubbed moga, or ‘Modern Girl’, by the Japanese journalists of the day.

The Modern Girl often wore Western-style clothing contemporary to her time, with short bobbed hair and knee-length skirts. That said, the majority of Japanese still preferred to remain in tradition Japanese dress.

With her newfound freedom and economic power, the Modern Girl went to the movies, smoked, drank and danced at the various jazz-infused dance halls that began to appear in the trendy Ginza district of 1920s Tokyo. She also, most shockingly, met up with men – unchaperoned — in public spaces. The Modern Girl is imagined to have had a succession of lovers prior to marriage (whether or not that was, in fact, the reality for most Japanese women at the time is another matter – but what is key is the idea of this was even entertained as a possibility).

Dance revues, jazz clubs, cafes and movie houses gave form to new a landscape of urban modernity. Working-class women found employment as café waitresses, while others worked as professional “taxi dancers” in the dance halls, where tickets for a 3-minute dance could be purchased.

Ian Buruma, a writer and academic working in the U.S. who focuses on the culture of Asia, described the social atmosphere of 1920’s Tokyo as “a skittish, sometimes nihilistic hedonism that brings Weimar Berlin to mind.” A tantalizing comparison can be made between interwar Japan and the short-lived Weimar Republic of Germany, with it’s famous brothels and cabarets of the prewar period. Similarly, Tokyo had the dance halls and cafes of the Ginza district, and its own decadent, jazz-listening pleasure seekers. It is within this atmosphere of newfound social freedom and modern pleasures that the “erotic grotesque” was born.

Next up, we’ll review the writings of Edogawa Rampo, the Godfather of Erotic Grotesque.

Pingback: Deviant Desires: Erotic Grotesque Nonsense, part II. Edogawa Rampo. | Lady Lazarus: dying is an art

Pingback: Deviant Desires: Erotic Grotesque Nonsense, Part V: “In the Realm of the Senses” | Lady Lazarus: dying is an art

Pingback: Someone asked me some questions about ero-guro, and here is what I answered. | Lady Lazarus: dying is an art

Pingback: Link, Zelda, and the Totalitarian State – The FYP site of Beverly Goh