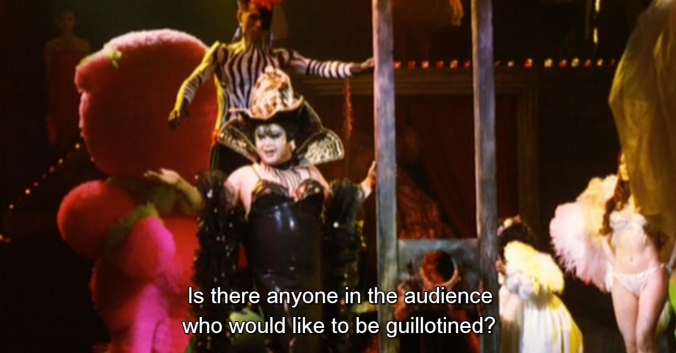

Happy holidays, dear readers. After a brief hiatus, I’ve returned to continue with my ongoing series relating to the Japanese cultural phenomenon called “ero-guro-nansensu”, or erotic-grotesque-nonsense. This blog post comprises Part VI of the series. You can read all of the previous instalments in the Ero Guro Nansensu category of my blog.

This post shall explore yet another film adaptation of Rampo: Yusuzo Masumura’s 1969 pinky violence film Blind Beast.

Blind Beast

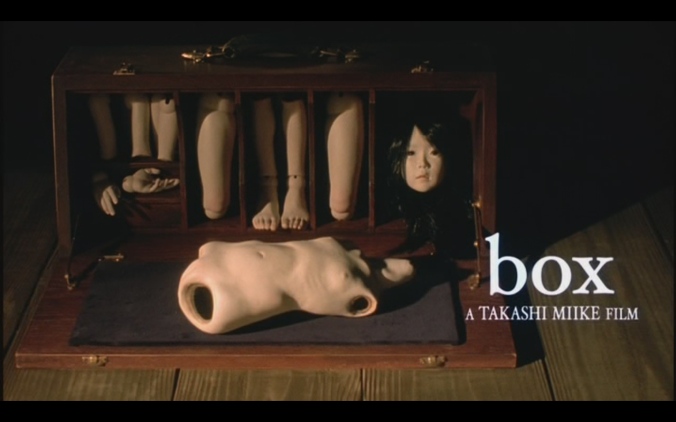

In Edogawa Rampo’s 1932 novella, a psychopathic blind sculptor named Michio disguises himself as a massage therapist in order to gain access to young women, whom he abducts. He sadistically murders and dismembers his victims, using their body parts to form strikingly realistic sculptures. He is described by as “crippled, ugly, leering, and with a seemingly endless internal catalog of perversities”. In Masumura’s film, the plot is simplified from many captive girls to a single one, and most of the unsettling and grotesque elements in Rampo’s story are stripped out. The filmmaker maintains the necessary blindness of his “beast” sculptor, but depicts him as significantly less monstrous, opting to make him more sympathetic to his audience.

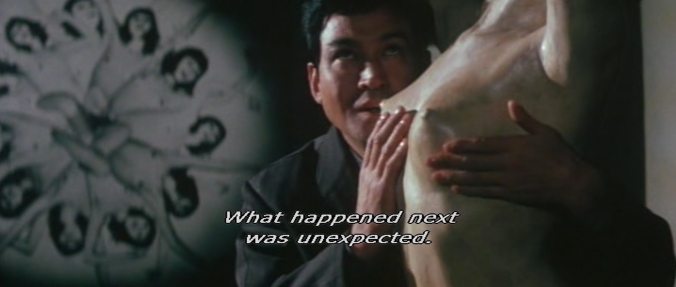

The film opens with a voiceover from a young artist’s model named Aki. She has arrived at an art gallery early in the morning for a meeting, and observes a lone gallery patron caressing a sculpted nude image of herself with a perverse intensity.

Aki notes as the man fondles the sculpture that she experiences the sensation of being touched on her own body. This notion of a sculpted “copy” with an otherworldly connection to the “original” body upon which it was based may relate back to the Rampo story. In the novella, the blind sculptor used the actual, severed body parts of his victims to form his sculptures. Masumura’s sculptor is much less monstrous. To create his sculptures, he only needs to feel his model in order to replicate her form. For him, the woman and her sculpted “double” are one and the same.

In the guise of a massage therapist, Michio gains access to Aki in her apartment. Determined to have her serve as model for him, he chloroforms her and, with the aid of his creepily attentive mother, carries her off to their secluded warehouse.

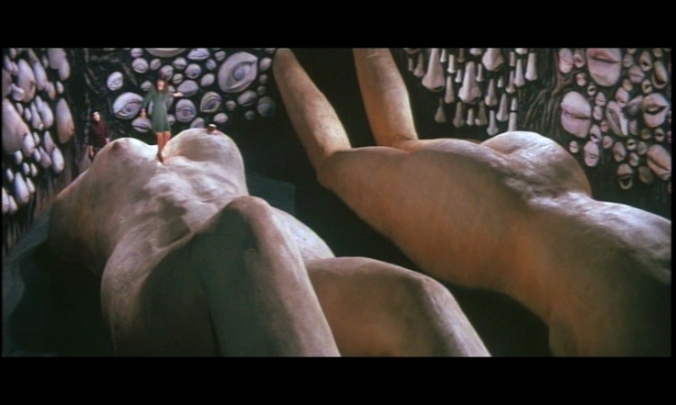

Aki awakens inside the dark interior of Michio’s cavernous studio. This is the scene that’s become emblematic of Blind Beast and, based on its set design alone, it’s easy to see why. As Michio delivers his lengthy backstory, director Masumura gradually reveals a surreal collection of sculpted body parts that adorn the walls of the studio.

The surreal body parts of Michio’s cavernous studio owe something of a debt to the famous set designed by Salvador Dali for Hitchcock’s film “Spellbound” (1945), although Dali’s set lacks the giant nipples.

After one failed escape attempt, Aki resigns herself to model for Michio, all the while seducing him in order to gain his trust. For his part, Michio is a naïve, child-like man whose knowledge of women is based solely on his relationship with his mother. Aki chides Michio for having “a baby’s view of women”, noting that his giant, recumbent female nude sculptures represent his very Oedipal view of Woman (suggesting a psychological urge to climb back into the womb). And, well, she does have a point.

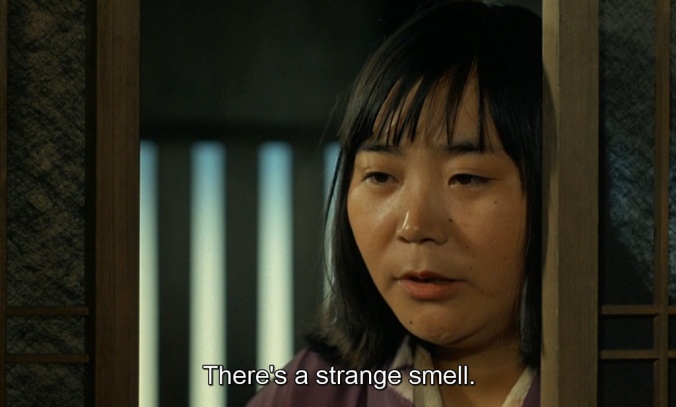

Aki skillfully manipulates Michio and turns him against his mother, whom Aki accuses of having an incestuously tinged love for her son. This enrages Mom, and a scuffle ensues. During the fight, Mom strikes her head and is conveniently dispatched. Aki attempts another escape, but is thwarted by Michio who drags her back into the lightless interior of his studio.

At this point, Masumura’s film makes a significant tonal shift from quirky black humour to something much more sinister. In order to demonstrate his masculinity — which had been called into question previously by Aki — Michio rapes her over several days. Improbably, Aki confesses (by way of voiceover) to having developed a “slight affection” for her rapist over this period of time. How should we read this? That Michio can only become an adult by conquering Aki and punishing her for belittling his manhood? Are we to understand that Aki shares Michio’s rape fantasy? These are questions that arise often when discussing “pink films”, and require an entire blog series on their own to explore and critique. Since Masumura’s Blind Beast is not a film deeply anchored in reality, I’m just going to acknowledge Aki’s highly problematic conversion from rape victim to willing sexual partner and move forward with the discussion, though I felt that some mention of it was warranted.

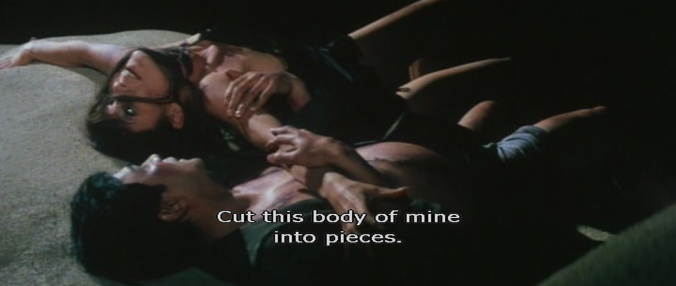

In the latter third of the film, the couple remain in the complete darkness of Michio’s studio where, unable to see, they explore the limits of the other senses through sex and increasingly violent, sadomasochistic acts such as biting, whipping and piercing the skin with Michio’s sharp sculpting tools. In this regard, they remind us of Sada and Kichi from In the Realm of the Senses, having removed themselves from the rest of the world to exist solely in their own universe of pleasure/pain sensuality.

Their sadomasochistic games culminate in extreme mutilation, when Aki requests that Michio amputate all of her limbs, rendering her a flesh-and-blood Venus de Milo much like the limbless female nude torsos that adorn Michio’s studio. Again, like Sada and Kichi, their exploration into the world of the senses cannot be perpetually sustained, and leads to their eventual demise. The world of the erotic-grotesque may provide a diversion from the real world and, for a time, a form of escape. It’s not a world, however, where one can set up a permanent residence.