A couple of months ago, I was interviewed in my studio by my friend and colleague, Lionel Bebbington. We shot a couple of hours of footage, during which I discussed my inspirations, craft and process. Here’s the completed, 12-minute video. Enjoy!

Ero Guro Nansensu

Posts relating to the Japanese cultural phenomenon “erotic grotesque nonsense”.

Wunderkammer

SYNOPSIS:

Madelaine’s cabinet of curiosities contained a collection of wonders to both delight and horrify. One day, a mysterious item in her cabinet captures her attention. A darkly-tinged fantasy that explores the erotic-grotesque.

Directed, animated, and edited by Jennifer Linton

Musical score by Zev Farber

ABOUT THIS FILM

Wunderkammer is a 2D stop-motion animated film shot under camera using unarmatured, replacement paper cutouts. This traditional animation medium involves hundreds of individual drawings that are drawn on paper, scanned, printed, hand-coloured and cutout. These cutouts are swapped in frame-to-frame to create smooth, complex movements not possible with articulated paper puppets. The resulting film has all the hand-drawn charm and personality of traditional cel animation, plus the lovely textures and materiality of stop-motion.

Many thanks to the kind generosity of my Indiegogo contributors!

Copyright ©2018 Papercut Pictures. All rights reserved.

Female-generated erotica, lost in translation.

Recently, I tripped across an online review for my animated short film La Petite Mort on a French-language arts & culture magazine called Wukali. At least, I think it’s a review. The reason for my uncertainty is, of course, the absolutely horrendous French-to-English translation offered by Google Chrome. The author, identified as Pierre-Alain Lèvy, seems to be discussing the difference between erotica — that classy, art-directed tease who promises, but never quite delivers — and her more hardcore sister, pornography. This discussion name-drops a short list of Western civilization’s erotic art heavy-hitters, including Apollonaire, André Breton and Octave Mirbeau — the latter best known for his written anthology of sadism entitled Torture Garden — and alludes to Charles Baudelaire through his mention of Flowers of Evil.

It is notable that most of the names mentioned in the article are 19th and early 20th-century French men (Lèvy also mentions male Japanese artists Dan Kanemitsu and Katsushika Hokusai). Conspicuously absent are the historical women artists working with erotic content. Even the most cursory glance back at the early 20th-century in France summons the names of celebrated women writers Anaïs Nin, Colette, and Pauline Réage (author of the BDSM-themed novel The Story of O), all of whom would serve as better antecedents to my female-generated erotica than either Mirbeau or Baudelaire.

That said, Lèvy does correctly detect the influence of Japanese erotic art on La Petite Mort. A tiny reproduction of The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife by Katsushika Hokusai is prominently placed within the frame, providing a strong hint at what’s to come in the narrative. As with many of my animation projects, the concept for the film began with a single image — the Hokusai print, in this case — and developed outwards from there. I asked myself questions such as: “What happened before that image? And what happened after?” The resulting animation is my response to those questions.

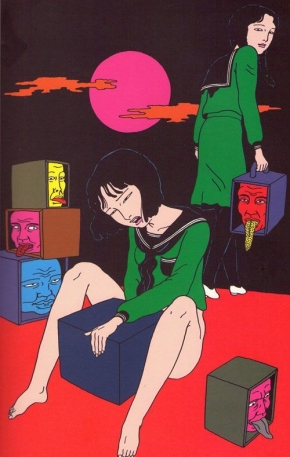

“Masturbation Box”, by Toshio Saeki.

A similar tactic was employed in the development of my most recent animation project Wunderkammer, which grew as a response to an image by Toshio Saeki from his print series Masturbation Box. An astute reader will have already noted that both the Japanese artists I’ve mentioned are men. Regrettably, there are very few Japanese women artists engaged with this type of ero-guro or “erotic-grotesque” imagery — at least, of which I am aware (Junko Mizuno is the one name that springs to mind, though I’d classify her work as more gothic kawaii than truly ero-guro). I consider my animations as female-lensed erotica engaged in a game of call-and-answer with the content produced by these male Japanese artists. Wunderkammer expands the universe surrounding Saeki’s image to a considerable degree, fleshing out the story with my other various fixations such as cabinets of curiosity, oddities, taxidermy, octopuses, and Edwardian-style costumes and furnishings. And, of course, that mysterious box.

Work-in-progress video still from “Wunderkammer” (projected release date Fall 2018).

Below is a screen capture of the Wukali article and here is a link to the original French article, which I imagine makes considerably more sense than the translated version offered here (if you can read French, that is).

Preview clip of “Wunderkammer”

Preview clip for “Wunderkammer”. from Jennifer Linton on Vimeo.

The entire film of Wunderkammer is under lock-and-key on Vimeo until it’s had a festival run, but you can get a taste of it in this clip. Very pleased with the original score composed by Zev Farber.

SYNOPSIS:

Madelaine’s cabinet of curiosities contained a collection of wonders to both delight and horrify. One day, a mysterious item in her cabinet captures her attention. A darkly-tinged, animated fantasy that explores the erotic-grotesque.

ABOUT THIS FILM

Wunderkammer is a 2D stop-motion animated film shot under camera using unarmatured, replacement paper cutouts. This traditional animation medium involves hundreds of individual drawings that are drawn on paper, scanned, printed, hand-coloured and cutout. These cutouts are swapped in frame-to-frame to create smooth, complex movements not possible with articulated paper puppets. The resulting film has all the hand-drawn charm and personality of traditional cel animation, plus the lovely textures and materiality of stop-motion.

Many thanks to the kind generosity of my Indiegogo contributors!

Copyright ©2018 Papercut Pictures. All rights reserved.

Interview with Shunga Gallery

Hello, gentle readers. Back in January of this year, I had the pleasure of being interviewed via email by the Shunga Gallery blog. Below is our conversation:

Shunga Gallery: I love the use of the intertitles in your subversive tales as they were added in the movies of the silent era. What appeals to you about this style?

Jennifer Linton: The intertitles serve a couple of purposes. As you mentioned, they call back to the era of silent film. The paper cutout-style of animation I’ve used is one of the earliest forms of stop-motion animation and would’ve been contemporary to films that employed intertitles. On a basic level, having inter titles meant that I didn’t need to incorporate a voiceover narration. Also, the poetic rhyming of the text nicely reinforced the Victorian-derived aesthetic of the film, and provided opportunity for humour.

SG: One of the paintings in the background of La Petite Mort is of Hokusai’s The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife. Also in both (and more of your) movies the octopus is an important character and a recurring theme. What’s your fascination with Hokusai’s print and the octopus in general?

JL: I’ve long held a fascination with a type of Japanese illustration that depicts ero-guro content. This type of content combines eroticism with absurd and grotesque elements. Hokusai’s famous shunga print predates the era of ero-guro-nansensu by over a century, but was highly influential on this later cultural material. The octopus is a fascinating creature; intelligent and beautifully alien to our eyes. The movement of an octopus’s tentacles looks great in an animation, which I one reason I use them so frequently.

SG: Also striking are the articulated figures in your movies. Is this for aesthetic or practical reasons? Are you familair with the articulated puppets used in the toy prints (shikake-e) in shunga ?

JL: The articulation of the paper puppets serves the practical purpose of allowing them to be animated, but I’m also a fan of the aesthetic of paper puppets. While the movement of such puppets can be stiff and unnatural, this stiffness works great with material that is surreal, fantastic and dream-like. Surprisingly, I was not previously familiar with shikake-e puppets! Thank you for alerting me to this tradition.

Video still from “Domestikia, Chapter 3: La Petite Mort”, 2013. Directed by Jennifer Linton.

SG: What movies and/or artworks had the greatest impact on you and your art and why?

JL: I’m a big cinephile, so there are many, many films and artworks that impact and influence me. My current animation project (entitled Wunderkammer) took an image from Toshio Saeki’s Masturbation Box as a creative jumping-off point, for instance.

Thank you Marijn at Shunga Gallery for the interview.

Deviant Desires: Erotic Grotesque Nonsense, part VII. “Caterpillar”, directed by Kōji Wakamatsu

This blog post is Part VII and the final instalment in my series on Ero Guro Nansensu. Click here to read the previous posts on this topic.

Caterpillar (2010), directed by Kōji Wakamatsu.

Wakamatsu is best known as the director of a number of pink films (pinku-eiga) in the 1960’s and has been called “the most important director to emerge in the pink film genre.” (He also, coincidentally enough, produced Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses). His adaptation of Edogawa Rampo’s short story Caterpillar belongs to a more recent trend in Japanese film to question their military past.

‘The Caterpillar’ (first published in 1934), was the only of Rampo’s stories to have been banned by the Japanese authorities. It was censored at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937) out of fear it would derail the nationalistic movement at the time.

The film opens with actual footage of Japanese soldiers during the Second Sino-Japanese War. In the original story by Rampo, Lt. Sunaga has been brought home from an unnamed war. Director Wakamatsu unambiguously attaches Rampo’s narrative to Japan’s war with China. Given the story’s previous history of censorship for being ‘anti-nationalist”, it is fitting that Wakamatsu uses Caterpillar as the set piece for his critique of Showa era ultranationalism.

After the war footage is shown during the title credits, we witness Lt. Kurokawa (Wakamatsu changes the names of the main characters) rape and murder a Chinese woman. While the event is not specifically named, this scene calls to mind Japanese war atrocities such as the infamous Nanking Massacre.

In late 1937, over a period of six weeks, Imperial Japanese Army forces brutally murdered hundreds of thousands of people–including both soldiers and civilians–in the Chinese city of Nanking. The horrific events are known as the Nanking Massacre or the Rape of Nanking, as between 20,000 and 80,000 women were sexually assaulted.

This added backstory of Lt. Kurokawa’s past transgressions (a detail not found in the Rampo text) frames Caterpillar partly as a tale of retribution. He has returned home a horribly disfigured quadruple amputee who is deaf and mute. He is, of course, completely dependent on his wife for all his physical needs, and he communicates these through a series of animalistic grunts and the use of his eyes. Given his condition, Kurokawa devolves into something less-than-human and, much like the caterpillar (whose form he now physically resembles), his entire existence focuses solely on food and sex.

Lt. Kurokawa is brought home to his family’s village with much pomp and ceremony, being praised as “an inspiration to all servicemen”. His family, however, appear more shocked and horrified than inspired. For the rest of the film, none of the characters dare acknowledge the “elephant in the room”, which is the fact that the celebrated War God is little more than a stump with a head attached. This element of absurdity is the strength behind Rampo’s short story, and director Wakamatsu underscores this with dry, deadpan humour.

Lt. Kurokawa’s wife Tadashi is burdened with the round-the-clock care of her husband, which is she expected to perform without complaint. This is the same husband who used to physically abuse her for failing to provide him with a son. Her only joy in an otherwise difficult existence are the occasional outings she makes with Kurokawa, whom she dresses in his uniform, his medals proudly displayed.

Wakamatsu’s film looks great, and is somewhat successful in fleshing-out the short story by Rampo. That said, it does feel stretched a bit thin. A 30-minute short might have been better for the Rampo story, rather than a feature-length film. It does, however, remain the most faithful adaptation of Rampo’s The Caterpillar currently set to film.

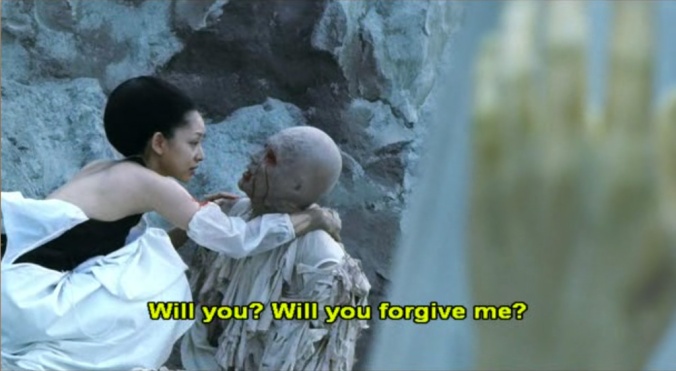

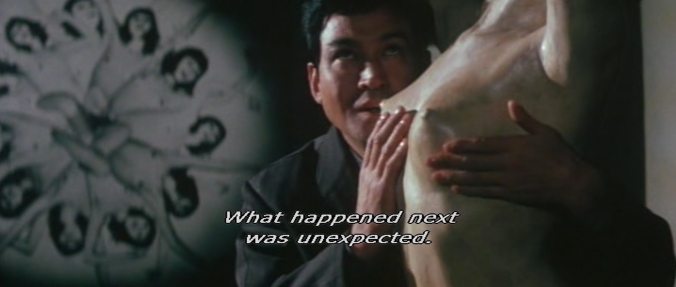

One interesting element to note about Rampo’s Caterpillar is that it very probably was the progenitor of amputee fetish (known clinically as acrotomophilia) as a favourite motif amongst current ero-guro content. This connection of amputee fetish to Rampo’s short story is made much more overt in Hisayasu Sato’s version of Caterpillar, a short segment he directed for the 2005 horror anthology Rampo Noir. Unlike Wakamatsu’s relatively faithful retelling of the Rampo text, Sato’s film focuses tightly on the highly eroticized, BDSM-flavoured power dynamic that exists between the limbless lieutenant and his wife — an element that is only a subtext in the Rampo story. While this turning-of-the-tables in terms of power dynamics is a key feature in Wakamatsu’s version, Sato’s impressionistic and considerably kinkier version deals with this to the exclusion of the rest of the story. Reminiscent of the film Boxing Helena, the lieutenant’s wife applies her surgical skills to render him her helpless and fully dependant sex slave.

Hisayasu Sato’s version of Caterpillar, directed for the 2005 horror anthology Rampo Noir.

Conclusion

Ero guro nansensu served as both a diversion and as a social “pressure valve” — absorbing all of the collective fears brought on by economic recessions, the Great Kanto Earthquake, growing militarism and political conflict, and the rapid social and cultural changes taking place within the Japan of the 1920’s and 30’s. These collective fears (and forbidden desires) were then given expression within the safe haven of ero guro’s imaginative play. The Modern Girl supplied ero guro with the intrepid heroine for its dark, erotically-tinged narratives, and the cafes and jazz-clubs provided the setting for these new, Modernist tales of the macabre.

Deviant Desires: Erotic Grotesque Nonsense, Part VI: “Blind Beast”

Happy holidays, dear readers. After a brief hiatus, I’ve returned to continue with my ongoing series relating to the Japanese cultural phenomenon called “ero-guro-nansensu”, or erotic-grotesque-nonsense. This blog post comprises Part VI of the series. You can read all of the previous instalments in the Ero Guro Nansensu category of my blog.

This post shall explore yet another film adaptation of Rampo: Yusuzo Masumura’s 1969 pinky violence film Blind Beast.

Blind Beast

In Edogawa Rampo’s 1932 novella, a psychopathic blind sculptor named Michio disguises himself as a massage therapist in order to gain access to young women, whom he abducts. He sadistically murders and dismembers his victims, using their body parts to form strikingly realistic sculptures. He is described by as “crippled, ugly, leering, and with a seemingly endless internal catalog of perversities”. In Masumura’s film, the plot is simplified from many captive girls to a single one, and most of the unsettling and grotesque elements in Rampo’s story are stripped out. The filmmaker maintains the necessary blindness of his “beast” sculptor, but depicts him as significantly less monstrous, opting to make him more sympathetic to his audience.

The film opens with a voiceover from a young artist’s model named Aki. She has arrived at an art gallery early in the morning for a meeting, and observes a lone gallery patron caressing a sculpted nude image of herself with a perverse intensity.

Aki notes as the man fondles the sculpture that she experiences the sensation of being touched on her own body. This notion of a sculpted “copy” with an otherworldly connection to the “original” body upon which it was based may relate back to the Rampo story. In the novella, the blind sculptor used the actual, severed body parts of his victims to form his sculptures. Masumura’s sculptor is much less monstrous. To create his sculptures, he only needs to feel his model in order to replicate her form. For him, the woman and her sculpted “double” are one and the same.

In the guise of a massage therapist, Michio gains access to Aki in her apartment. Determined to have her serve as model for him, he chloroforms her and, with the aid of his creepily attentive mother, carries her off to their secluded warehouse.

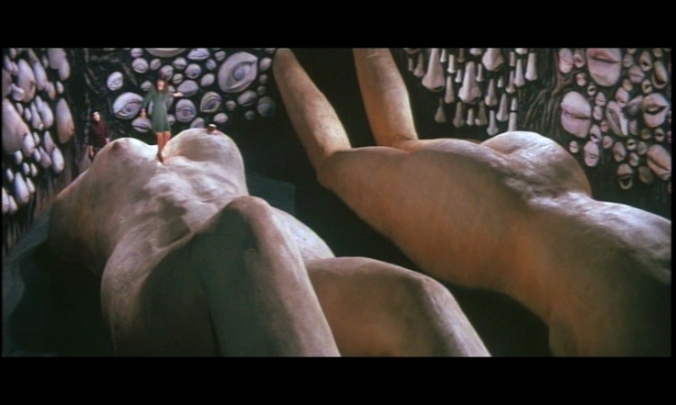

Aki awakens inside the dark interior of Michio’s cavernous studio. This is the scene that’s become emblematic of Blind Beast and, based on its set design alone, it’s easy to see why. As Michio delivers his lengthy backstory, director Masumura gradually reveals a surreal collection of sculpted body parts that adorn the walls of the studio.

The surreal body parts of Michio’s cavernous studio owe something of a debt to the famous set designed by Salvador Dali for Hitchcock’s film “Spellbound” (1945), although Dali’s set lacks the giant nipples.

After one failed escape attempt, Aki resigns herself to model for Michio, all the while seducing him in order to gain his trust. For his part, Michio is a naïve, child-like man whose knowledge of women is based solely on his relationship with his mother. Aki chides Michio for having “a baby’s view of women”, noting that his giant, recumbent female nude sculptures represent his very Oedipal view of Woman (suggesting a psychological urge to climb back into the womb). And, well, she does have a point.

Aki skillfully manipulates Michio and turns him against his mother, whom Aki accuses of having an incestuously tinged love for her son. This enrages Mom, and a scuffle ensues. During the fight, Mom strikes her head and is conveniently dispatched. Aki attempts another escape, but is thwarted by Michio who drags her back into the lightless interior of his studio.

At this point, Masumura’s film makes a significant tonal shift from quirky black humour to something much more sinister. In order to demonstrate his masculinity — which had been called into question previously by Aki — Michio rapes her over several days. Improbably, Aki confesses (by way of voiceover) to having developed a “slight affection” for her rapist over this period of time. How should we read this? That Michio can only become an adult by conquering Aki and punishing her for belittling his manhood? Are we to understand that Aki shares Michio’s rape fantasy? These are questions that arise often when discussing “pink films”, and require an entire blog series on their own to explore and critique. Since Masumura’s Blind Beast is not a film deeply anchored in reality, I’m just going to acknowledge Aki’s highly problematic conversion from rape victim to willing sexual partner and move forward with the discussion, though I felt that some mention of it was warranted.

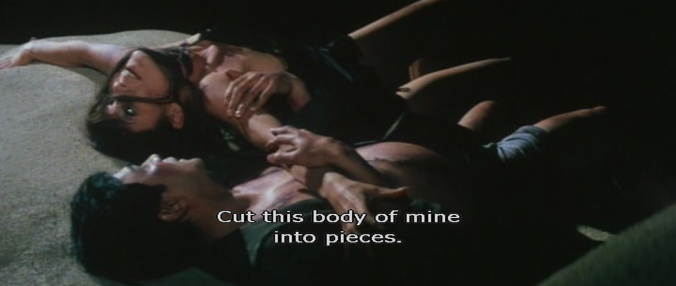

In the latter third of the film, the couple remain in the complete darkness of Michio’s studio where, unable to see, they explore the limits of the other senses through sex and increasingly violent, sadomasochistic acts such as biting, whipping and piercing the skin with Michio’s sharp sculpting tools. In this regard, they remind us of Sada and Kichi from In the Realm of the Senses, having removed themselves from the rest of the world to exist solely in their own universe of pleasure/pain sensuality.

Their sadomasochistic games culminate in extreme mutilation, when Aki requests that Michio amputate all of her limbs, rendering her a flesh-and-blood Venus de Milo much like the limbless female nude torsos that adorn Michio’s studio. Again, like Sada and Kichi, their exploration into the world of the senses cannot be perpetually sustained, and leads to their eventual demise. The world of the erotic-grotesque may provide a diversion from the real world and, for a time, a form of escape. It’s not a world, however, where one can set up a permanent residence.

Someone asked me some questions about ero-guro, and here’s what I answered.

I recently received a message via my Facebook Page regarding some of the ero guro nansensu-themed posts on this blog. I felt that the questions raised were so pertinent to my ongoing discussion on the subject, that I should fashion a blog post around them. Many thanks to Christo KJ for the original message.

Q: Hi, I hope you don’t mind that I’m contacting you like this. I’ve been studying film and television science for the past five years here in Norway. I just read your posts about ero guro nansensu and I found it very interesting. But I do have some questions about the definition of what an ero guro film is.

Both Italian Neorealism and German Expressionism have very specific rules for what type of movies that are and are not part those movements. Ero guro is of course not a film movement like Neorealism. But are there any similar rules when it comes to ero guro in film, which explains specifically what is and what is not ero guro?

A: That’s an excellent question. The short answer is: no, and yes.

No, in that ero guro nansensu emerged as a mass-media driven cultural phenomenon at a time when the film industry in Japan was still in its early years** and, as you so rightly pointed out, was not a film movement like German Expressionism — which, incidentally, emerged at roughly same time in Germany as ero guro flourished in Japan.

Ero Guro could be best described as a zeitgeist — or “spirit of the times” — that organically developed during the interwar years in Japan. It’s main devotees were the urban youth, artists, and other bohemians, although its influence was also felt outside of the cosmopolitan city centres. It was not a movement created by a group of artists, nor was it guided by a manifesto of any kind that outlined its common goals or philosophy.

Academics like Miriam Silverberg and Jim Reichert have proposed that ero guro formed a kind of collective reaction against the ultraconservative morality touted by the fascists who were rising to power in 1920s-30s Japan. This interpretation of cultural history does seem to carry credibility, and I wrote about this in my previous blog entry.

With all that said, there are some motifs and themes that I would identify as being strongly indictative of ero-guro. These are:

- the circus, and the circus sideshow “freak”

- the dangerous double, or doppelgänger

- “something horrible hidden in plain view”

- “deviant” sexualities: fetishes, paraphilias, shibari

- grotesqueries such as malformed bodies, missing limbs, deformity

- disguises and secret identities

- a crime, especially a bizarre and excessively gruesome one

- insanity, obsession

- absurdity, nonsense, dark humour

Most of these motifs come directly from the writings of Edogawa Rampo, about whom I wrote in another blog entry. You simply cannot discuss ero-guro in any meaningful way without touching upon the work of Rampo.

Q: Are all pink films that contain torture or S&M ero guro?

A: I would argue no, though there does seem to be a lack of consensus on how best to apply the ero-guro label to films. In my opinion, the term ero-guro (sometimes shortened to simply guro) is thrown around too indiscriminately. Since Rampo and his literary contemporaries were so heavily influential in the shaping of ero-guro, I use their work as a gauge against which all work labeled ero-guro is measured. Whereas Teruo Ishii’s pinky violence film Horrors of Malformed Men is undoubtedly ero-guro — partly owing to the fact that it’s a very loose adaptation of at least five different Rampo stories — not all violent pinku-eiga can be categorized as ero-guro. In other words, even though sex, violence and gore are frequently elements found in ero-guro, their presence alone does not indicate a film that is ero-guro.

To confuse matters further, however, I recently stumbled upon this classification of ero-guro-nansensu in a book entitled Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema, written by Jasper Sharp:

“The term [ero-guro] resurfaced in the 1950s to describe the more macabre B-movie gangster, science fiction, and horror works by Shintoho, such as those directed by Ishii Teruo, as well as screen adaptations of writers like Rampo. From the 1980s onward, it has been most commonly used in connection with underground works featuring overt depictions of sex, violence, and grotesquerie…” — Sharp, pp. 60-61

Ultimately, it may come down to personal taste as to which version of ero-guro you prefer. I hold a greater affinity towards the artistry, complex plot twists and exaggerated theatricality of films such as Sion Sono’s Strange Circus (2005), versus the more straightforward softcore-meets-gore of Entrails of a Virgin (1986). Both films deliver on the sex, violence and gore, but Strange Circus does it with a lot more style and panache.

“Strange Circus”, 2005, dir. Sion Sono.

Q: The Guinea Pig movies by Hideshi Hino have been labeled as ero guro (Directory of world cinema: Japan p.251). The two first movies in this series have little to no plot, it’s just about an hour of torture. So what is the difference between ero guro and Japanese torture porn?

A: I strongly disagree with the categorization of The Guinea Pig films as ero-guro. I would simply label them Japanese torture porn. As you point out, there’s little or no plot. Ero-guro films not only have plot, but they often have very elaborate, convoluted plots.

Q: Would you consider the movie Grotesque by Koji Shiraishi as ero guro?

A: I’m aware of that film, but have yet to view it.

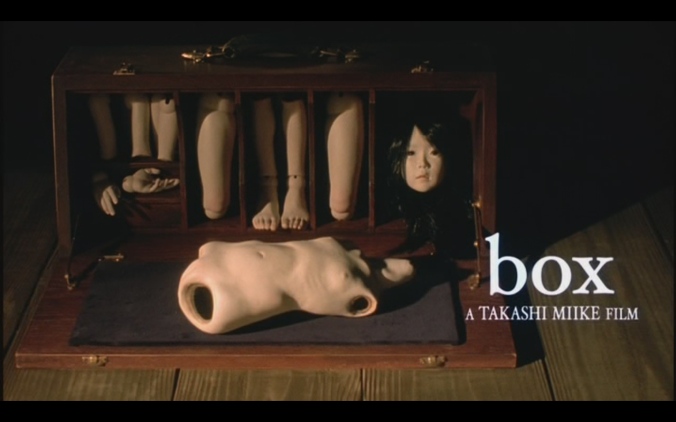

Q: Would you consider some of Takashi Miike’s movies as ero guro, for example Ichi the killer, Gozu, Visitor Q?

A: Takashi Miike has created a couple of films that I would identify as being ero-guro, but not amongst the films you mention. There’s an excellent pan-Asian compilation DVD called Three…Extremes that came out in 2004 which featured a short film by Miike called Box. A dream-like, atmospheric story that’s uncharacteristically restrained for Miike, Box involves the story of twin girls who work with their father in a magic act. Their trick is to fold themselves into impossibly small boxes. There’s the hint of incest (deviant sexuality), bodies that do not conform to convention (the girls are contortionists), murderous revenge and blurred boundaries between the dreaming and waking world. It’s by far the most ero-guro flavoured film that Miike has done to date. You can get a taste of it here.

Q: Are there any non-Japanese films that you would consider as ero guro, like for example Pasolini’s Salo 120 days of Sodom or A Serbian film?

I haven’t seen either of those films, so I can’t comment. I tried watching Salo once, and found it impossibly boring. I know enough about A Serbian Film to know that I need never watch it.“Newborn porn”? No thanks.

Some ero-guro films that I would recommend:

- Strange Circus

- Box

- Imprint

- Horrors of Malformed Men

- Midori — the Girl in the Freak Show

- Blind Beast

- Caterpillar

- In the Realm of the Senses

- Sada Abe

- Rampo Noir

**Interestingly enough, Japan was one of the first countries to develop a film industry, beginning in the latter years of the 19th-century.

Tentacled Animated GIF

Just made this animated GIF for an erotic art tumblr project. Thought I’d share. Feel free to post on your tumblr site, or wherever you see fit.

Lady Lazarus’s “Ero Guro” Board on Pinterest

Hello, gentle readers. For those of you who are following my series of ero guro themed posts and can’t quite get enough, I have a special treat. Lady Lazarus has been collecting images on Pinterest for her Ero Guro board. Want to learn more about contemporary artists who work with ero guro themes and subjects? Are you a fan of artists such as Junko Mizuno, Takato Yamamoto, Suehiro Maruo, and Toshio Saeki? Then click on the image below and visit my Pinterest board.

NSFW, but of course you knew that. Nothing too porny, though. This is a classy operation.