This is Part V of my ongoing series of posts relating to the Japanese cultural phenomenon called “ero-guro-nansensu”, or erotic-grotesque-nonsense. You can read all of the previous instalments in the Ero Guro Nansensu category of my blog. The previous post, which discussed Midori — The Girl in the Freak Show, can be found here.

Actors Tatsuya Fuji and Eiko Matsuda in Nagisa Oshima’s controversial “In the Realm of the Senses” (1976).

The next film I’d like to discuss in my ongoing series on ero-guro-nansensu is one of the most notorious Japanese films ever made, In the Realm of the Senses (1976), directed by the “bad boy” of the Japanese New Wave, Nagisa Oshima.

“Japanese cinema’s preeminent taboo buster, Nagisa Oshima directed, between 1959 and 1999, more than twenty groundbreaking features. For Oshima, film was a form of activism, a way of shaking up the status quo. Uninterested in the traditional Japanese cinema of such popular filmmakers as Kurosawa and Ozu, Oshima focused not on classical themes of good and evil or domesticity but on outcasts, gangsters, murderers, rapists, sexual deviants, and the politically marginalized.”

— (Text excerpted from an essay written for the Criterion collection on Oshima)

This pedigree of Japanese cinema’s “bad boy” makes Oshima an excellent candidate to direct a film adaptation of the already lurid true story of the famous ero-guro era murderess Sada Abe. In 1936 Tokyo, Sada Abe worked as a maid in a restaurant owned by Kichizo Ishida with whom she became romantically involved. After a brief but intense sexual fling, Abe erotically asphyxiates Ishida, afterwards cutting off his penis and testicles and carrying them around with her in her handbag. Abe was eventually arrested and convicted of murder in the second degree and mutilation of a corpse. She was sentenced to six years in prison, and was released after five.

Newspaper photo taken shortly after Abe’s arrest, at Takanawa Police Station, Tokyo on May 20, 1936.

Pre-WWII writings, such as the text The Psychological Diagnosis of Abe Sada (1937) depict Abe as an example of the dangers of unbridled female sexuality and as a threat to the patriarchal system. In the postwar era, however, she was treated as a critic of totalitarianism, and a symbol of freedom from oppressive political ideologies (from Wikipedia). And thus enters the director Nagisa Oshima. The story of Sada Abe, and the persona that developed around her as a “symbol of freedom from oppression” would, of course, speak to the political aims of Oshima. In The Realm of The Senses uses sex as a radical act against the oppression of personal liberty.

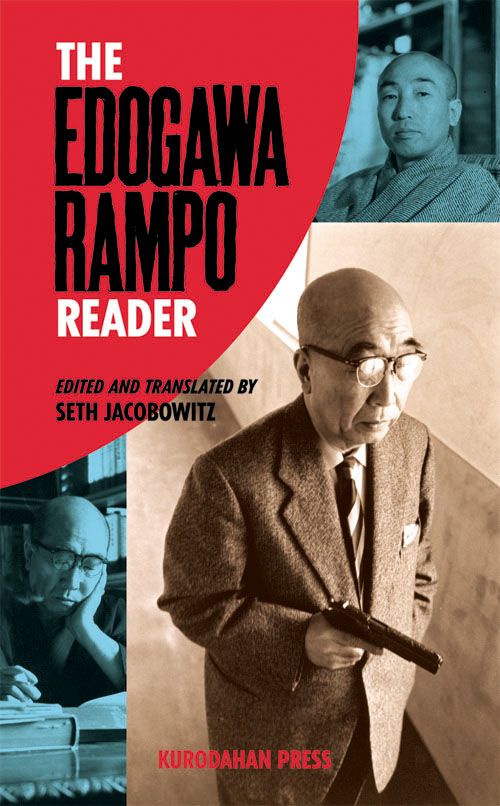

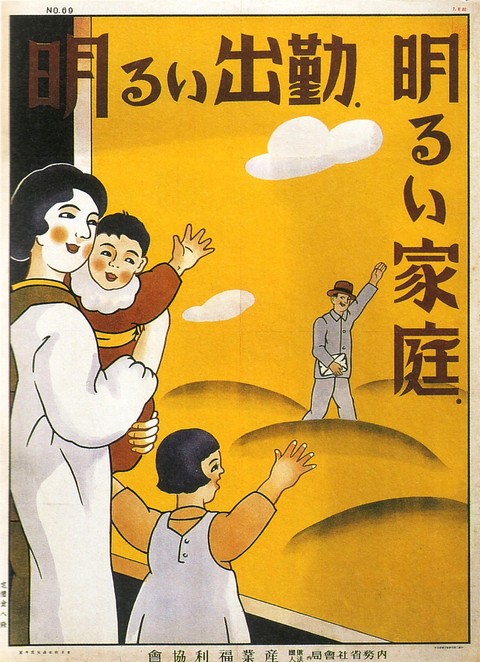

If we recall the fascist propaganda poster I included in my introductory post on ero-guro, we can observe that it clearly promoted a very conservative morality of procreative sex between married couples for the purpose of begetting a new generation of Japanese (all for the purpose of ‘nation-building’). The sex we see depicted between the two main characters in Oshima’s film, Kichi and Sada, is the opposite of that. Theirs is not socially sanctioned sex. They are not husband and wife, and Kichi is already married with children. Once their romantic fling begins, they leave the restaurant and hole up inside a nearby inn – thus removing themselves from society and their prescribed roles within in. Their self-imposed exile, and Kichizo’s eventual death, can be see as the ultimate “opt-out” from the ultranationalist agenda and to Imperial Japan.

Why was In The Realm of The Senses so controversial when it was released in 1976? The film features scenes of unsimulated sex between the two main actors, which is quite daring for a filmmaker who’s known as an auteur, rather than a pornographer. In fact, Oshima was charged in his native county with obscenity, and had to go to court to defend his film (charges were subsequently dropped in 1982). Oshima used the language of pornography, but did not create a purely pornographic film. If the aim of pornography is to titillate for the purposes of arousal, then In The Realm of The Senses does not function as pornography. We, the audience, may watch Sada and Kichi have sex, but the camera never places us within the action. We watch at a certain remove. Additionally, the actors in the film are never objectified, reduced to mere performers of sex for our voyeuristic consumption. We empathize with them. Unlike the objectified and dehumanized porn actors, these actors seem very real and very human to us.

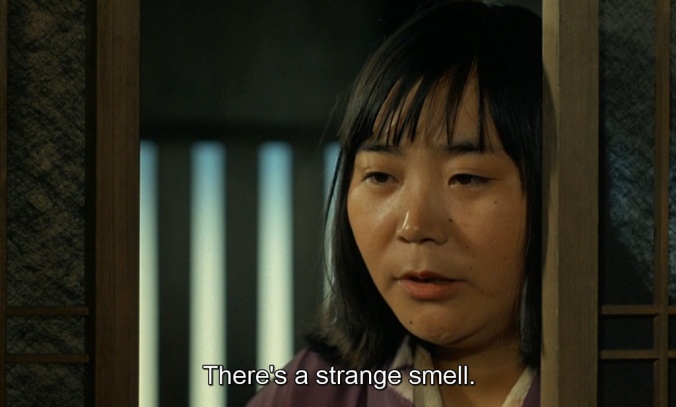

The sex between Sada and Kichi is also very visceral. There is no gloss of romanticism or soft-focus lens here – this is real sex that results in the release of bodily fluids, with the resultant wet spots on the futon and funky smells which permeate the inn room in which Kichi and Sada temporarily reside (and which is commented on by the maids who have to clean their room).

At the beginning of the clip below, we see Sada departing from her meeting with her former school principal, with whom she periodically has sex for money as a means of support for herself and Kichizo. The principal (rather ungallantly) points out that she “smells like a dead rat”, which we could read as either relating back to the state of complete physical abandon that Kichi and Sada have entered, or could be foreshadowing of Kichi’s death. Later, when Sada reunites with Kichi, she is visibly shaken by the fact that the maids have cleaned the room in their absence. The inn room had functioned as their oasis from the world, but now the outside world was creeping back in and imposing its order and control.

We see Kichi step out from a barber shop and into an empty street. A platoon of soldiers approaches and Kichi walks in opposition (in the opposite direction) to the soldiers. The next instant, a crowd of flag-waving townsfolk materialize. We can only read this scene as symbolic. Kichi is isolated, walking on a different side of the street from the rest of Japan. There is no place for him in Imperial Japan, and he knows it.

The erotic-asphyxiation that Sada and Kichi engage in originates from their mutually shared desire to explore extreme sensory experiences. Eventually, of course, this co-mingling of death with sex leads to Kichi’s wish to transcend this world.

Next in this series of posts, Yasuzô Masumura’s “Blind Beast.”