I wrote the following essay on American visual artist Hannah Wilke for an art history class in graduate school. I include the full text and images, excluding citations. If you’re a student who discovers this via search engine, then I have every confidence in your research abilities to track down the scholarly sources. Wilke was a seminal Second Wave feminist artist whose work has received renewed interest from scholars since her death in 1993.

The politics of inclusion that shaped feminist discourse in the 1960s and 1970s spawned a legacy of body-based performance art, much of which was associated with women artists who used their own face as a subject of continual exploration. The self- imaging of women artists such as the provocative American artist Hannah Wilke was frequently attacked and dismissed by art critics as being indulgent exercises in narcissism that only served to reinforce the objectification of the female body. The charge of narcissism leveled on Wilke and her work may have been warranted, however, this should not be considered as a pejorative. Rather, the narcissism of Wilke can be viewed as a shrewd feminist tactic of self-objectification aimed at reclaiming the eroticized female body from the exclusive domain of male sexual desire. The ‘self-love’ of narcissism is a necessary component to this reclaiming of the body and the assertion of a female erotic will as being distinct from that of the male artist. Wilke wielded her narcissistic self-love as a powerful tool of critique, defiantly placing her own image into the hallowed halls of the male-dominated art institution.

The term “narcissism” derives from the ancient Greek myth of Narcissus, a beautiful but arrogant youth who cruelly spurned the love of his admirers. For his cruelty, he was cursed by the goddess Nemesis and fell in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. The doomed Narcissus pined away for his unattainable lover – the image of his own self – and literally died as a result of his amorous longing.

Sigmund Freud bestowed the name of this mythic Greek youth upon his psychoanalytic theory of narcissism, a theory that describes normal personality development. According to Freud, the self-love of narcissism is a normal complement to the development of a healthy ego. Whereas a certain amount of narcissism is desirable, an excess of self-love is considered dysfunctional and indicative of pathology. This latter definition of narcissism, the one of pathological self-absorption, has cast our current understanding of narcissism in a negative light and reinforced the use of the term as a pejorative.

The psychoanalytic theories of Freud suggest that negative or pathological narcissism is a specifically female perversion. Art critic Amelia Jones writes that “[d]rawing loosely on Freud’s definitions – which connect narcissism to both a stage of development and to a form of homosexual neurosis – narcissism has come in everyday parlance to mean simply a kind of “self-love” epitomized through woman’s obsession with her own appearance.” Hence, the charges of narcissism leveled on Hannah Wilke were attempts by the critics to summarily dismiss her work as mere manifestations of a woman’s obsessive self-love and infer, according to Jones, that Wilke’s art was not “successfully feminist.”

Critics such as Amelia Jones and Joanna Frueh have championed Wilke and proposed, through their respective writings, a new and positive view of narcissism as a legitimately feminist, subversive tactic in the making of art. In her catalogue essay entitled “Intra-Venus and Hannah Wilke’s Feminist Narcissism”, Jones contextualized Wilke’s work within the framework of her “radical narcissism” and argued that the use of her own image throughout her art is far from the conventional or passively ‘feminine’ depiction of women as seen in advertising and other forms of mass media. Joanna Frueh, in her essay that accompanied the 1989 Wilke retrospective in Missouri, equated Wilke’s “positive narcissism” with a form of feminist self-exploration and an assertion of a female erotic will. Both Frueh and Jones cogently argue for a “positive narcissism” that expunges itself of the negative connotations of Freudian psychoanalytic theory and, in contrast, actively and unapologetically engages in self-love. Wilke enacts an aggressive form of narcissistic self-imaging that defiantly solicits the patriarchal gaze which she then, as Jones writes, “graft[s] onto and into her body/self, taking hold of it and reflecting it back to expose and exacerbate its reciprocity.”

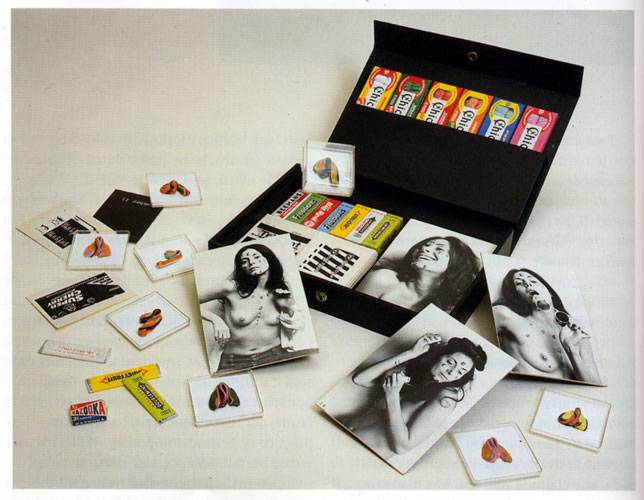

Fig. #1. Hannah Wilke. "S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication". Mixed media (artist's multiple). 1974-75.

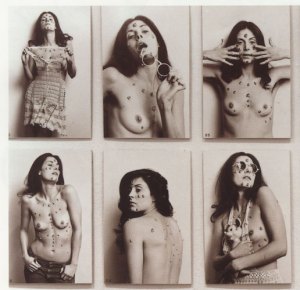

Wilke’s active solicitation of the “male gaze” as a method of feminist critique is best exemplified in her photographic series entitled S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication (figs. 1-2), a series which had been originally produced as a box-set artist’s multiple for the 1975 exhibition “Artists Make Toys” at the Clocktower in New York. Wilke commissioned a commercial photographer to capture her semi-nude self-portraits in which she adopts the exaggerated postures of the celebrity and fashion industries. In one such photograph, a sunglass-wearing Wilke clutches her Mickey Mouse toy tight to her partly naked torso as she gazes off-camera at an imaginary paparazzi. She assumed the role of the celebrity art “star” suggested by the witty wordplay of her title S.O.S. Starification Object Series. As with many of Wilke’s titles – for she was fond of linguistic games and frequently engaged in puns – there is a double meaning to be found in the titular pun “starification.” Wilke dotted her own skin with several tiny vaginal sculptures that she had shaped from chewing gum. These small sculptures decorated her body in a manner recalling the practice of ritual scarification employed by certain African cultures as a means of beautification. Given the presence of the vaginal “scars” in combination with the sexy, glamourous black and white photographs of Wilke, it is not difficult to locate the artist’s critical stance on the occasionally painful regimens Western women inflict upon themselves in their conformity to accepted conventions of beauty. Wilke willfully submitted her own body to this ritualized, albeit pretend, self-abuse in order to address this “tyranny of Venus” which, as Susan Brownmiller writes in Femininity, “…a woman feels whenever she criticizes her appearance for not conforming to prevailing erotic standards.” The fact that Wilke herself was, by these same erotic standards, a beautiful and sexually desirable woman does not confuse her aim of critique but rather serves to strengthen her commentary on women’s roles and gender stereotypes. Her overstated, sultry expressions and postures of sexual display invite scrutiny. Wilke was keenly aware of her status as a celebrity art-star as well as a beautiful, eroticized object of desire and she capitalized on both with the S.O.S. Starification Object Series. The original dissemination of this photographic series in a packaged box set, complete with sticks of chewing gum, preformed gum vaginas and phalluses, and the semi-nude artist self- portraits, simultaneously commented on both the artist-celebrity as a commodity as well as the erotic consumption of the female body. Cleverly, Wilke underscored the erotic self-objectification of her image in the extended title for this box set multiple: S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication. We are reminded that this is an adult game, and Wilke’s use of the word mastication in reference to chewing (gum) is likely a pun on masturbation, a suggestion that locates her eroticized self-portraits on the parameters of pornography.

Fig. #2. Hannah Wilke. "S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication". Detail. Mixed media (artist's multiple). 1974-75.

Assimilating the visual language of the objectified female body, Wilke employed her own eroticized body as a metaphorical mirror that she then held up to reflect back the sexual projections of male desire. This act of reflection enabled Wilke to sever her passive (and traditionally female) receptiveness of this male projection and assert her own erotic will. In her collection of essays entitled Erotic Faculties, Joanna Freuh used the phrase “autoerotic autonomy” in reference to Wilke’s images and suggested that her “…self-exhibition may demonstrate the positive narcissism – self- love – that masculinist eros has all but erased.” The empty vessel that is the celebrity or the fashion model – devoid of a personal will as she functions as a receptacle for our projected desires – has been adopted and systematically absorbed by Wilke’s exaggerated poses. For her part, Wilke then engaged her narcissistic self-love as a means to fill these empty vessels with her aggressive sexuality. The sites of female erotic pleasure, namely the mouth and the vagina, are conjured in her chewing gum sculptures while, at the same moment, they hint at the violent aggression of the folkloric vagina dentata.

The consciously sexualized self-objectification of Wilke and the use of her own body as a “professional currency” often elicited harsh criticism from the ranks of feminism, an ideology to which she actively subscribed. Lucy Lippard, the champion of 1970s feminist art, famously wrote that Wilke’s “confusion of her roles as beautiful woman and artist, as flirt and feminist, has resulted at times in politically ambiguous manifestations that have exposed her to criticism on a personal as well as on an artistic level.” Art critics Judith Barry and Sandy Flitterman dismiss Wilke’s self-portraits: “In objectifying herself as she does, in assuming the conventions associated with a stripper, …Wilke…does not make her own position clear…It seems her work ends up by reinforcing what it intends to subvert…” The tense political climate and rapid social change of America during the decades of the 1960s and 70s fueled a radical activism amongst Second Wave feminists. The urgency felt by these activists to affect social change in relation to gender equality frequently generated a feminism that was fervent, even orthodox, in its ideology. This strict orthodoxy was shaped by anti- essentialism – a philosophical stance that rejected the representation of the female body as it was believed too imbued with a history of objectification by male artists – and therefore unable and unwilling to accommodate the sexualized body-based art of Hannah Wilke. The negative reception of Wilke by critics like Lippard, Barry and Flitterman may have been prompted by an adherence to this strict orthodoxy. The complex and ambiguous views of the body and female sexuality that Wilke presented, at times even contradictory to the aims of feminism, generated rancor in this inflexible climate of anti-essentialism.

In her 1978 interview “Artist Hannah Wilke Talks with Ernst” the artist unapologetically spoke of the “ethics of ambiguity” that characterized both her work and life. She addressed, in her honest and unmediated manner, the conflicted views of a woman who, though conscious of feminism, still felt concerned with her appearance and desirability to men. Rather than deny this impulse, Wilke embraced her feminine narcissism and brandished it as a weapon. Such a bold act of defiance and deliberate provocation against the anti-essentialist feminism that dominated the 1960s and 70s later established Wilke as the “…spiritual parent to postfeminist artists such as Tracey Emin…” and anticipated the self-imaging of Janine Antoni and Cindy Sherman.

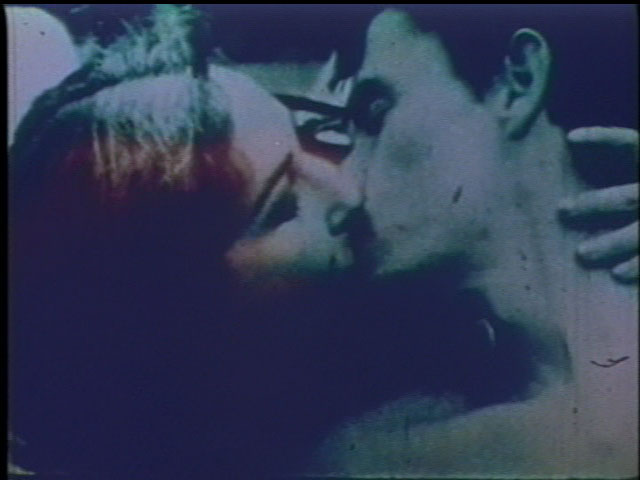

Wilke was not the only woman artist of her generation to use her own body in a consciously sexualized manner, nor was she the only artist to engage with narcissism as a feminist tactic. Carolee Schneeman’s canonical 1965 Fuses (fig. 3), a film that included photographic footage of the artist having sex with her then-partner James Tenny, was greeted with outrage from the feminist audience who, as film theorist Shana MacDonald writes, “…[were] uncertain how to incorporate the sexualized, erotic and self-produced image provided by Schneemann” Similar to the harsh criticisms leveled on the photographs of Wilke, the erotic self-portraiture of Schneemann’s Fuses was frequently attacked as being “obscene and narcissistic.” According to MacDonald, it was her sexually graphic imagery – imagery that feminist theorists found indistinguishable from the objectified female image being resisted – that caused Schneemann to be misunderstood by her peers and ultimately marginalized.

As the coquettish semi-nudes of Wilke’s S.O.S. Starification Object Series made reference to imagery generated for pornographic use, so too does Schneemann’s Fuses address pornography in order to critique its traditional objectification of women. The repeated, non-linear narrative of Fuses interrupts the pornographic convention that the film necessarily terminate in the obligatory “cum shot” of male ejaculation. The sexuality communicated by Schneemann’s film is highly subjective and anchored in the banal reality of the everyday, including shots of the artist’s cat and the domestic surroundings of her home. The subjectivity of Fuses was further heightened by the literal mark of the artist, evidenced in Schneemann’s use of hand-processing techniques such as collage, painting and scratching directly onto the celluloid. Her infusion of a personal subjectivity performed as a feminist resistance against the sexual- objectification of the female body as seen in conventional pornography. By simultaneously inhabiting the roles of both the image and the image-maker, she positioned herself “not as sex object, but as willed and erotic subject, commanding her own image.” Schneemann’s urge to see her own sexualized image is a manifestation of self-love and the hypothesized “positive narcissism” of Jones and Freuh. As Narcissus romantically yearned for his own image, Schneemann desires to view her own erotic image, not reflected in a pool of water, but projected larger-than-life on the theatre screen. This act is a bold assertion of her narcissism and erotic will.

At first glance Wilke’s S.O.S. Starification Object Series, much like Schneemann’s Fuses, appeared to reinforce the visual language of the objectified female body. The sultry eyes, seductively parted lips and naked breasts of Wilke read as cultural signifiers of female sexual invitation and availability. Lippard may have been correct in her observation that Wilke played both the “feminist and flirt” but her assessment that this polarity stemmed from her confusion over these two roles was essentially wrong. Wilke’s narcissistic self-imaging was not, as Elizabeth Hess charged, an impulse to “…wallow in cultural obsessions with the female body,” but a pointed feminist critique of these same obsessions. In contrast to fashion models and pin-up girls, who passively offer their flesh to be inscribed by male desire, Wilke interrupted this erotic exchange by the presence of her chewing gum “scar” sculptures. Recalling the artistic intervention of Schneemann’s hand-processing techniques in Fuses, Wilke’s sculptures mark the otherwise unblemished surface of her skin and disrupt the easy consumption of her body as an erotic object. She declared the canvas of her skin as the terrain of her own erotic expression, and marked it accordingly. Whereas the youth Narcissus failed to possess his own beloved self-image, Schneemann and Wilke are too shrewd in the deployment of their narcissism to suffer this same fate.

Women artists of the late 1960s and 1970s, such as Schneemann and Wilke, often engaged in the feminist project of reclaiming the female body from previous male privilege. Centuries of depiction by exclusively male artists had rendered the female nude a dehumanized, neutral object. Wilke and her feminist contemporaries sought to rectify this situation by seizing creative control over one’s own body. Performative works such as Wilke’s 1974 Gestures (fig. 4) – a video that featured the artist sculpting her flesh – enact this reclamation by proposing the artist’s own body as an artistic medium.

The thirty-minute black-and-white video Gestures showcases Wilke, her head and shoulders tightly framed, performing a series of repeated, often exaggerated gestures and facial expressions. These gestures are often absurd and comical in nature, while others verge on sexual seduction. A silent Wilke gently pulls and kneads her own face, manipulating her youthful, elastic skin much like the soft, putty-like material of her chewing gum sculptures. Saundra Goldman observed that Gestures “…signaled [Wilke’s] transition from sculpture to performance,” and there is a cyclical component to this transition: the soft, pliable chewing gum that Wilke employed to approximate flesh was now being mimicked by the artist’s own skin.

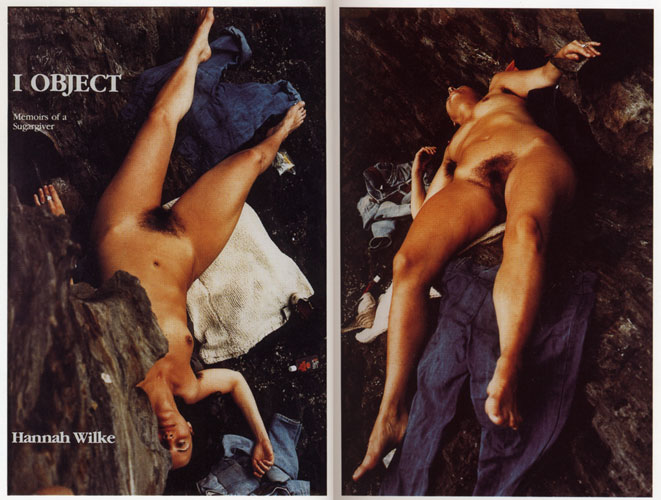

The reclamation of the female body from the privileged control by male artists was the primary motivation behind Wilke’s photographic diptych entitled I OBJECT: Memoirs of a Sugargiver (fig. 5). Wilke’s strong objection was directly aimed at the father of the avant-garde, Marcel Duchamp. While the box set of S.O.S. Starification Object Series offered a critical view of consumerism, the fashion industry and pornography, and Gestures a declaration of control over one’s own body, the faux book jacket of I OBJECT was a direct response to Duchamp’s static rape victim of his infamous diorama Etant donnès (fig. 6). In her 1988 conversation with Joanna Freuh, Wilke stated: “I find Etant donnès repulsive, which is perhaps its message. She has a distorted vagina.” The pun contained in the title I OBJECT, with the play on the word “object” as both noun and verb, laid the foundation for the critical feminist dialogue Wilke embarked upon with this heavy-weight of art history.

The sculptural diorama Etant donnès confronts the viewer with a rustic wooden door, riddled with small holes. A light source shines through these holes, enticing the viewer to peek through and witness a scene hitherto concealed. A pastoral, natural landscape is suddenly revealed, in the foreground of which an alarmingly pale, naked female torso lies inert amongst a bramble of dried twigs and leaves. Her legs are splayed open to reveal her strangely misshapen vagina. The exposed nakedness of the woman, her corpse-like stillness and her derelict location amongst the bramble imply violation and victimhood. As if in a final gesture of violence, Duchamp has chosen to frame the woman’s image within the peepholes of the door in such a manner as to visually decapitate her. The mechanism of display – namely the peepholes through which the scene is revealed – forces the viewer to assume the role of voyeur, further compounding the violation of the woman.

Wilke’s I OBJECT functions as both homage and a critical response to Duchamp: she believed that “to honor Duchamp is to oppose him.” Taken while on a family vacation in Spain, the glossy colour photographs of Wilke show the artist, fully nude, lying atop some discarded clothing on a large, craggy rock. One of the photographs that comprise this diptych approximates the pose of Duchamp’s female torso, with Wilke’s body foreshortened in the camera lens so that her pubic region dominates the picture plane. In stark contrast to the deathly paleness of the woman in Etant donnès, Wilke appears whole-limbed, healthy and tanned. The clothing upon which she lies may have been voluntarily shed in a moment of spontaneous sexual activity, or simply in the act of sunbathing. A bottle of suntan lotion that lies nearby seems to support the latter. The second photograph of the diptych shows Wilke staring upwards at the camera, and directly at the viewer, her face partly concealed by a rocky outcropping. A small but satisfied smile adorns her face. The superimposed text reads “I OBJECT: Memoirs of a Sugargiver” across the upper left portion of the image and then “Hannah Wilke” on the lower left, in close juxtaposition to her smiling face. The presence of her written name paired with her direct, outward gaze reads like a radical declaration of personhood, as if to say I am Hannah Wilke, and here is my body. The feminist gesture of “positive narcissism” comes strongly into play in this particular context. Wilke’s feminist response to the faceless victim of Etant donnès is a bold affirmation of both her personhood and her female sexuality.

As previously mentioned, the close association of women to narcissism partly derives from a loose interpretation of Freudian theory that linked a “woman’s obsession with her own appearance” with a form of psychoanalytic pathology. This association is highly relevant in the critical reception of a work of art; a crucial factor to consider is the gender of the artist. Lucy Lippard, the same art critic who, ironically, dismissed Wilke for being a “feminist and flirt”, denounced the gender divide that existed between the reception of body-based performance work created by male artists against similar work produced by women. “She is a narcissist,” Lippard wrote of women artists, “and Vito Acconci with his less romantic image and pimply back, is an artist.” The crucial distinction between the narcissism of Vito Acconci and Hannah Wilke – for as Rosalind Krauss effectively argues in her essay “Video: the Aesthetics of Narcissism”, Acconci was most assuredly a narcissist – lies in the feminist agenda that fuelled the narcissism of Wilke.

Vito Acconci’s performance-based work often contains ambiguous narratives that frequently wander into the territory of the absurd and contradictory. Much like his contemporary Hannah Wilke, Acconci primarily used his own body as an artistic medium. In his 1972 video entitled Undertone (fig. 7), Acconci is as conspicuously aware of performing as Wilke was of posing in her multitudinous self-images. Undertone begins with Acconci seating himself at a table, the opposite end of which extends in the direction of the camera. This arrangement immediately implicates the camera/viewer into the scene. Acconci closes his eyes, placing his hands on his thighs, and repeatedly mumbles an awkwardly confessional sexual fantasy involving an imagined woman who lurks beneath the table: I want to believe there’s a girl here under the table…who’s resting her hands on my knees…she’s resting her forearms on my thighs…slowly, slowly rubbing my thighs… After several repetitions of this fantasy, Acconci suddenly pauses, straightens his body and stares directly out at the camera/viewer. His hands, now resting on the table top, are clasped together in a pleading gesture while he repeatedly intones: I need you to be sitting there…facing me…because I have to have someone to talk to…so I know there’s someone there to address this to… Acconci proceeds to again close his eyes and place his hands beneath the table. Resuming his mumbled confession, he contradicts his original narrative by stating: I want to believe there’s no one under the table…I want to believe…it’s me that’s rubbing my thighs… The video concludes with a final plea to the viewer to witness the revelation of his fantasy.

Comparable to the revealing titles of Wilke, the layered meanings behind Acconci’s title Undertone provides an important clue to its interpretation. The Concise Oxford Dictionary defines the word undertone as an “underlying quality; undercurrent of feeling.” The underlying theme of Acconci’s video is not found in his repeated sexual fantasy of the imaginary woman under the table – a fiction that his monologue later negates – but rather in his urgent plea directed at the viewer. Acconci compels the viewer to witness his confessional fantasy and thus, by acting in this capacity, participate. A necessary reciprocity exists between Acconci’s performance and the viewer’s reception of this fictitious fantasy. A fruitful comparison can be drawn between Acconci’s Undertone and Wilke’s Gestures video. The performance of Acconci is validated by an exchange with the viewer in the same manner as the poses of Wilke require an onlooker. Equally, both artists achieve a form of sexual power through their performative actions. The crucial difference lies in gender. Even as the awkward disclosure of the fantasy ostensibly renders him vulnerable, Acconci nonetheless seizes sexual control. He punctuates the revelation of his fantasy by a vigorous and masturbatory rubbing of his own thighs, a gesture that creates an uncomfortable tension in the viewer who has been manoeuvred into the place of the voyeur. His repeated pleas to the viewer to witness recall the dynamic of the sexual exhibitionist who requires an onlooker to fulfill his perversion. Acconci enacts his narcissism by forcing his passive-aggressive sexuality upon the viewer.

In the video Gestures, Wilke systematically performs the postures of female display. She seductively rubs her finger across her upper lip. With the practiced smile of a fashion model, she repeatedly tosses her long hair in simulation of a shampoo commercial. Isolated from their usual context of seduction or advertising, these gestures appear absurd – which is entirely Wilke’s point. By repeatedly and methodically performing these gestures, she empties them of meaning. As a young, desirable woman Wilke understands that sexual display is the currency of her power. As a feminist, she acknowledges that these same gestures reduce her to a mere sex object. There is an implicit solicitation of the viewer to witness Wilke’s repetitive actions in much the same manner as Acconci’s Undertone requests participation with his narrative. Their respective sexual power – Wilke as the female sex object and Acconci as the male sexual exhibitionist – require the gaze of the viewer to activate this power exchange.

The deliberate self-objectification of Hannah Wilke seems, in the context of contemporary art practice, very prescient indeed. A consummate agitator and provocateur, her legacy of complex and eroticized body-based art anticipated the work of numerous future women artists whose creative point-of-departure was their own visage. While her work may have been devalued by feminist critics of her generation, a renewed interest from the ranks of feminist scholarship has emerged since her untimely death from lymphoma in 1993. Wilke and her feminist colleague Carolee Schneemann, who worked similarly with erotic self-portraiture, shrewdly engaged with the self-love of positive narcissism to reclaim the erotic female body from the objectification of the male gaze. Fully comfortable within her own skin and embracing all of her very human contradictions – as an artist, a feminist and a woman – she skillfully commanded her own image, both in front of and behind the camera.

Pingback: Some girls are more lethal than others: that deadly ‘vagina dentata’ grin. | Lady Lazarus: dying is an art

Hello,

This is a great essay! It’s been one of the better sources that I’ve found and the most comprehensive account of Wilke’s work. It would be great if you could provide more specific information on you, as the author (mainly, your name, school, degree, and year) since you’ll certainly need to be sourced in an essay that I’m currently working on.

Thanks so much!! I really appreciate it,

Lisa

Thank you. Here’s my details: Jennifer Linton, essay entitled “Feminist Narcissism and the reclamation of the erotic body” written and submitted for her graduate studies class in contemporary art theory at York University, Toronto, Ontario (Canada) in May 2009. I’ve since graduate with my MFA in Visual Arts for York University.

Dear Jennifer,

I just sent you an email as well. I was thrilled to read this essay (yes, it came up in a Google search). I’m also looking for your bibliography if you wouldn’t mind. It would be very helpful for a paper I’m currently working on for my Art History class: Women in the Visual Arts. I’m researching Hannah Wilke and specifically focusing on the theme of narcissism. I thank you in advance– I really appreciate the help. Congrats on such a beautifully written and incredibly interesting essay.

Best regards,

Lucy Morgan

Reblogged this on Lady Lazarus: dying is an art and commented:

The month of February is quickly being swallowed up by my teaching & an exhibition of my art taking place on the 24th. Here’s a repost of an earlier entry on the late American artist Hannah Wilke. She was a busy person, too.

Pingback: the art of hannah wilke: ‘feminist narcissism’ and the reclamation of the erotic body | fleurmach

Pingback: the art of hannah wilke: ‘feminist narcissism’ and the reclamation of the erotic body | quae

Pingback: The art of Hannah Wilke: ‘Feminist Narcissism’ and the reclamation of the erotic body. « Belief or Truth?

Dear scholars:

Please feel free to cite my paper for any assignments you’re working on. You can find my details in the comment above. Please do not, however, ask for the endnotes and bibliography. I’m sorry if that creates a problem with citation from my essay, but plagiarism *is* a serious academic offense. Thanks for your understanding — Jennifer Linton

Pingback: Happy Birthday Hannah Wilke (1940-1993) - Not the Singularity - Not the Singularity

Pingback: DonaVita

Dear Jennifer,

I found your essay on my searches and it came really useful for my understanding of feminism art. I live in Iran and because of to many problems women got here it is essential to understand feminism art and how to use it as an social tool.

I am trying to write a critique on one of the best installation exhibition took place by an artist which has many points explainable with feminism viewpoint.

I found out there is a explanatory article by Joanna Frueh named “The Body Through Women’s Eyes.” Unfortunately I couldn’t find in on the Internet and there is no way I can reach its paper version in Iran.

I would be really thankful if you could send it to me via E-mail.

Hi Soha. Regarding the Joanna Frueh essay you mention, I don’t believe that the entire essay can be found online. Maybe you could reach out to the author at her web site: http://www.joannafrueh.com/

Here’s the book in which it’s featured: “”The Body through Women’s Eyes,” in The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s;

History and Impact, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: Abrams, 1994), 190-207.

There are some very good academic books on feminist art free on Google Books, like this one: http://books.google.ca/books?id=-szcP80gKckC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Also, Joanna Frueh’s “Erotic Faculties” http://books.google.ca/books?id=aWlJwh8bmOEC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Joanna+Frueh&hl=en&sa=X&ei=UvnGUpvDDsG4yQGQjYHQCw&ved=0CDgQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=Joanna%20Frueh&f=false

Thanks a lot,

ممنونم

Pingback: Appropriation/Recreation Notes – Erin Butrica

Pingback: The Body Beautiful – Midnight at the Oasis