The last (I promise) of the grad school essays I shall inflict upon you. In this one, my task was to compare my work with that of another contemporary visual artist. I chose Shary Boyle. The astute among you will recognize a passage or two from my Master’s thesis in this essay. Hey, it’s not plagarism when you cannibalize your own writing.

Throughout history, visual artists have fleshed out mythological subjects and generated images based on traditional, time-honoured stories. Myths supply an accessible and universal narrative to which the artist can attach a personal story. Renowned scholar and mythologist Joseph Campbell describes one of the goals of myth as “…effecting a reconciliation of the individual consciousness with the universal will.” Similarly, in his essay “The Expressive Fallacy” Hal Foster cites Nietzsche’s discussion of an artist’s use of myth to express an interior world: “The whole notion of an ‘inner experience’ enters our consciousness only after it has found a language that the individual understands – i.e., a translation of a situation into a familiar situation…” The “language” to which Nietzsche refers can be interpreted as “mythology” which provides a universal narrative to which all cultures, no matter how disparate, have access. The “inner experience” may be read as the personal, psychological or emotional world that the artist seeks to materialize through the use of myth. In short, myths connect us to each other by anchoring the idiosyncrasy of the individual to a universally shared point of reference.

In my own art practice, I frequently make use of myths and archetypes as cultural ready-mades into which I insert my own personal history and meanings. Myths are reinterpreted in my work from a feminist perspective that considers gender representation in these mythological narratives. Another contemporary Canadian artist who employs a similar creative, feminist tactic is Shary Boyle. A commonality in our work is the use of female mythological subjects that evoke the traditional, allegorical link between women and nature. Rather than simply offer a critique of the feminized concept of nature, however, both Boyle and myself use motifs derived from nature in a subversive manner that transform our female subjects in strange, fantastic ways. The transformations and mutations that our mythological heroines experience provide the visible, external evidence of their inner psychological and emotional world.

In her work prior to 2008, Boyle’s use of fairytales and mythological subjects tended to be global rather than specific. Her phantasmagoric imagery suggested the realm of dreams and myths without representing a particular legend or cultural tradition. Her two pencil and gouache drawings that we shall examine, both dating from 2003 and simply called Untitled, are evidence of her generalized incorporation of myth. Both drawings involve remarkable incidents in which a single female figure, isolated on the white void of the paper, quietly experiences a magical transformation. In Untitled (fig. 1) we are confronted with a woman in a bright red dress sitting contentedly in the grass, hands resting peacefully in her lap. The drawing is linear and economical; the grass on which the woman sits is minimally drawn. Two long, yellow plant stalks topped with white blossoms grow outwards from the eye sockets of the woman, a strange phenomenon that has not managed to disturb her serenity. The very fact that the woman appears unconcerned by this fantastic event seems to suggest that this transformation is metaphoric as the flowers are a manifestation of an interior psychological state. Equally, the woman may have simply acquiesced to the inevitability of this strange transformation. The subject of Boyle’s second drawing Untitled (fig. 2), a prepubescent girl whose rigid stance and sideways glance suggests that she’s somewhat more alarmed by the tangled bush growing out from her mouth, nevertheless seems to accept the strangeness of this event as normative.

In her essay entitled “Ornamental Impulse”, art writer Josée Drouin-Brisebois comments on Boyle’s surreal transformations as a manifestation of the emotional and psychological worlds of her subjects. “Boyle’s [figures]”, says Drouin-Brisebois, “express the inner life of the emotions materially.” Drouin-Brisebois cites the review of art critic Robin Laurence for Boyle’s paintings Companions (2004), wherein Laurence states: “Boyle’s portraits suggest that what looks outwardly freakish in others is the metaphorical equivalent of inward aspects of all our characteristics and circumstances.” Thus, the plant life that blooms from the bodily orifices of these female subjects is emblematic of their interior states, though what precisely those states would be remain vague and mysterious.

The mythology to which Boyle attaches her idiosyncratic narratives serves to anchor the work in tradition and provide the viewer with visual clues as to how one might interpret her dream-like imagery. For instance, the otherworldly flora of these drawings reference allegorical and mythological associations of women to nature. Rather than challenge the traditional dichotomy of women and nature, Boyle embraces it in a subversive manner. According to Drouin-Brisebois, Boyle’s women “become…nature in unsettling ways – verdancy out of control or a parasite that takes over the body…” Boyle acknowledges the allegorical tradition while at the same time engaging a sinister playfulness that alters it.

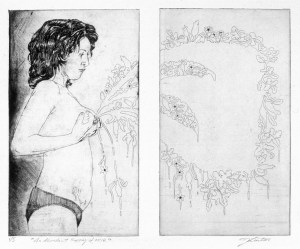

Similar to Boyle, otherworldly flora plays a prominent role in my 2006 intaglio print entitled An Abundant Supply of Milk (fig. 3). Whereas Boyle rarely identifies her female subjects as aspects of herself, my work makes frequent use of self-portraiture and is characterized by an autobiographical content. This particular self-portrait shows myself standing in profile, naked save for a pair of underwear. With my hands I squeeze my breasts and produce an exaggeratedly large spray of breast milk. This cloud-like spray of breast milk, in turn, blossoms into a soggy mass of flowers. Like the drawings of Boyle discussed earlier, this print recognizes the mythic association between women and nature, and in particular the concept of a nurturing “mother nature”, while at the same time subverting it. The nourishing food that is breast milk has transformed into a bizarre floral mass that, rather than natural, appears inexorably alien. Created in the months that followed becoming a first-time mother, this image addressed my response to the strange transformations enacted upon my body as a result of pregnancy and childbirth. The milk-flowers that spring forth from my breasts represent an externalization of the estrangement I felt from my own body.

A second, earlier self-portrait speaks not to a feeling of estrangement but to the human impulse towards creation, both in art as well as in procreation. The coloured pencil drawing entitled Genesis (fig.4) illustrates the growth of a leafy, magenta and orange plant stalk out of my opened mouth. This fanciful stalk terminates in a perfectly round, ripe pomegranate fruit. Similar to the heroines of Boyle’s drawings, my visage appears untroubled by the unconventional growth of this fruit as if this were the result of a natural, internal process. In contrast to Boyle’s 2003 Untitled drawings, however, the magical vegetation of Genesis recalls a very specific mythological story while at the same time evoking the women-nature dichotomy. The appearance of the pomegranate in this drawing is highly significant as it is a direct quotation from an earlier body of work in which I assumed the role of Persephone, a tragic heroine from Greco-Roman mythology. This role-playing allowed for the insertion of personalized content within the larger context of a universal narrative. Or, as Nietzsche expressed, the myth of Persephone provided “…a translation of a situation into a familiar situation.” We will return to this discussion of Persephone after an introduction to Boyle’s latest works, one of which, coincidentally, deals directly with this same myth.

As previously stated, Boyle’s work is frequently characterized by a global adoption of mythology, her imagery an amalgam of different mythic traditions synthesized with her own idiosyncratic symbolism. The recent unveiling of Boyle’s latest porcelain sculptures at the 2008 grand reopening of the Art Gallery of Ontario, however, provides an exciting and atypical exception to this aspect of her work. Boyle was commissioned by the AGO to create work that responded to the gallery’s permanent collection. She selected two 18th-century Italian bronze statuettes by Giovanni Battista Foggini with which to engage in a conversation across history. The subjects of Foggini’s sculptures are two commonly depicted Greco-Roman myths: Perseus slaying Medusa and The Rape of Proserpine. Boyle’s porcelains offer feminist reinterpretations of these myths while simultaneously maintaining her characteristic surreal imagery that hints at the internal, psychological world of her subjects.

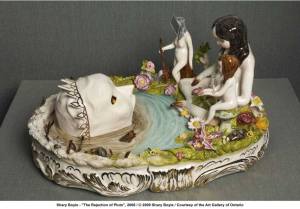

Boyle’s response to Foggini’s The Rape of Proserpine re-imagines the Greco-Roman myth upon which it is based and addresses the violent and sexually problematic subject matter of the original Baroque bronze. Her delicate porcelain sculpture entitled The Rejection of Pluto (fig. 5) casts the titular deity as a hideously yawning monster and not the sinewy, handsome abductor of Foggini’s statuette. In her 2008 interview with art critic Sarah Milroy featured in The Globe and Mail, Boyle discussed the responsibility she felt as a feminist artist in rendering an alternate version of this classical myth: “I guess I just felt that this subject matter had to be engaged. I had been asked inside the museum, and I felt a kind of responsibility to interrupt some of those narratives, to propose some other kinds of stories.”

Proserpine is the Roman goddess of springtime, wife of Pluto and mythological equivalent of the Greek goddess Persephone. Her story is one of great emotional power: an innocent maiden abducted by the lustful god of the Underworld and forced to become his bride. In the Globe and Mail interview, Boyle related the version of this Greco-Roman myth that inspired her reinterpretation:

“…Pluto, the Lord of the Underworld, fell in love with Proserpine, the beautiful daughter of the harvest goddess. Lust incarnate, he emerges from Hades through a pond in the glade of the water nymph Cyane, wreaking havoc on this sacred sylvan spot and seizing Proserpine by force, making her his bride in Hell. Cyane, who protects the natural realms, weeps tears over this loss, so much so that her tears replenish the landscape Pluto has devastated.”

The scene of Boyle’s The Rejection of Pluto is the idyllic glade of the water nymph Cyane, decorated with exotic flowers, seashells and fairytale toadstools. The monstrous head of Pluto emerges from the water, his cavernous mouth yawning open as if to swallow his intended victim. Bright red-orange light, suggestive of the flames of Hell, flickers inside the mouth and eyes of the hollow, chasmal head. The water that immediately surrounds Pluto’s head appears brown and putrid and the vegetation bleached white, all vitality having been drained out by its proximity to the god of the Underworld. The female characters of this story – the girl-child Proserpine, her mother Demeter, and the nymph Cyane – are all gathered in a group at the opposite end of the glade. The amphibious water nymph Cyane glowers fiercely at Pluto, defending Proserpine whom Boyle has cast as a small child wounded by mirrored shards. According to Boyle, these three female figures “represent emotional, mental and physical resistance under siege.”

The crucial role that nature plays in The Rejection of Pluto can be likened to that of Boyle’s 2003 Untitled drawings, although the correlation between women and nature in the sculpture have been further strengthened. The landscape of The Rejection of Pluto reflects the violation suffered by Proserpine through its transformation from lush verdancy to polluted wasteland. This transformation of the landscape symbolizes Proserpine’s psychological and emotional turmoil in much the same manner as the mirrored shards that have pierced her flesh represent her physical violation. Boyle’s shrewd interpretation of the Proserpine/Persephone myth emphasizes the allegorical link between women and nature in her analysis of the mistreatment of both women and nature in the world.

The tragic heroine Persephone has also been depicted as a prepubescent girl in my 2000 mixed-media drawing entitled The Bitter Seed. In this drawing, I combine an image of myself as a child with the myth of Persephone as a means to address the difficult territory of childhood sexual abuse. By adopting the role of the mythological heroine, I translate and universalize my personal experience. Through the use of this metaphor, I strive to make an emotional state palatable and thus more easily approachable by the viewer.

The Bitter Seed takes its name from the pomegranate seed that Persephone was forced to eat, thus sealing her fate as the goddess whose annual death and rebirth would usher in the changing seasons:

“Persephone was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of agriculture. Hades, the lord of the Underworld, surprised Persephone one day while she was picking flowers and carried her off to be his bride. Demeter, the distraught mother, threatens to destroy all mortal men by causing an endless drought unless her daughter is returned. Zeus, who is the king of the gods at Olympus, commands Hermes to fetch Persephone from the realm of Hades. The wise Hades chooses to obey the command of Zeus; however, before Persephone is returned, he tricks her into eating a seed from a pomegranate. This deception is later revealed when Demeter asks her daughter “…have you eaten any food while you were below? If you have not, even though you have been in the company of loathsome Hades, you will live with me and your father…but if you have…you will return again beneath the depths of the earth and live there a third of the year; the other two-thirds of the time you will spend with me…”

To the ancient Greeks, the myth of Demeter and Persephone served to explain the death and regeneration of plant life each year. The metaphoric link between women and nature is quite overt: Persephone personifies the cycle of the seasons through her annual sacrifice.

In The Bitter Seed, my childhood self stands thickly outlined in black against a brightly coloured background reminiscent of a stained-glass window. One of my hands holds aloft a pomegranate, above which hangs the phrase “dirty girl.” I stare quizzically at both the fruit and the phrase, my child mind unable to fully grasp their meaning. Like the pomegranate in the Persephone myth, the fruit I hold represents violation and entrapment. Similar to the girl-child Proserpine in Boyle’s sculpture, who displays her wounded arms for the consideration of the viewer, my child-self in The Bitter Seed holds the pomegranate up as a symbolic manifestation of inner “wounds”.

Fig. 6. Jennifer Linton, "St. Ursula and the Gorgon’s Head", coloured pencil and drawing ink on Mylar, 62 cm x 80 cm, 2002.

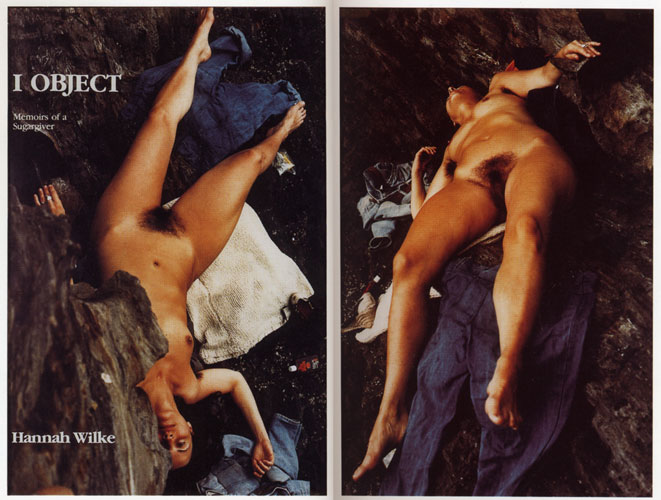

The victimization of the girl-child Persephone in The Bitter Seed is later redressed in my 2002 drawing St. Ursula and the Gorgon’s Head (fig. 6) in which I assumed the role of the Catholic Saint Ursula, the patron saint of schoolgirls. In a manner similar to The Bitter Seed, this drawing blended autobiographical elements with mythological role-playing in order to universalize personal experience. The heroine of St. Ursula and the Gorgon’s Head assimilates two divergent mythological traditions: the hagiography of the Catholic saint with the Greco-Roman myth of the Gorgon Medusa. More avenging angel than saint, St. Ursula is shown adorned with angel wings and holding aloft a sword and the severed head of Medusa. The mouth of the snake-haired Medusa gapes open in a silent scream while a magical bloom of red flowers bleed from the wound of the severed neck. In the background, graphic and highly stylized red flowers also appear to bleed. Much like the strange, sinister flowers of Boyle’s 2003 Untitled drawings, these violent blossoms subvert the traditional woman-nature dichotomy and the association of women with a passive and nurturing feminine principle.

Women are frequently cast as the prize at the end of the hero’s quest but are seldom depicted as the active, adventurous hero themselves in mythology. This gender-biased tradition was best summarized by Joseph Campbell in his 1982 interview with Rozanne Zucchet from his collected writings entitled “The Hero’s Journey”:

“I was teaching these courses on mythology and at the end of my last year there this woman comes in and sits down and says, ‘Well, Mr. Campbell, you’ve been talking about the hero. But what about the woman?’ I said, ‘The woman’s the mother of the hero; she’s the goal of the hero’s achieving; she’s the protectress of the hero; she is this, she is that. What more do you want?’ She said, ‘I want to be the hero!’ So I was glad that I was retiring that year and not going to teach any more [audience laughter].”

While Campbell’s anecdote evidently amused his audience, it also underscores the gender discrimination inherent in mythological models. The sword-wielding heroine of St. Ursula and the Gorgon’s Head constitutes my feminist response to Campbell and this gender-biased tradition. My heroine adopts the stance traditionally occupied by the male hero Perseus who, as the Greek myth tells us, beheaded the female monster Medusa. Additionally, the gender of Medusa in my drawing has been switched from female to male as the image of the severed gorgon’s head my heroine holds is, in fact, a direct visual quotation of a painting by Caravaggio where Medusa is uncharacteristically portrayed as male.

The representation of gender also plays a crucial role in Boyle’s second porcelain sculpture commissioned by the Art Gallery of Ontario. Entitled To Colonize the Moon (fig. 7), this sculpture encapsulates her response to Foggini’s bronze statuette Perseus Slaying Medusa as well as to the traditional Greco-Roman myth that she “has interpreted in light of both her environmentalist and feminist ideas.” Boyle’s reinterpretation of the myth views Medusa as a “very misunderstood monster” who suffers a number of indignities and violations resulting from the capricious cruelty of the Olympian gods. The severed head of Medusa lies atop a funeral pyre comprised of dead bats and bees, the expression on her lifeless face one of sad resignation to her tragic fate. In stark contrast to the heroic romanticism of Foggini’s Perseus, Boyle’s version of the Greek hero is a lily-skinned, rosy-cheeked effeminate boy who sits in quiet repose while he wipes the blood from his sword. This traditionally triumphal moment has been undercut by the calmness of the scene and soft, unheroic body of Boyle’s Perseus. The violence of the story is not celebrated, but merely represented in an anticlimactic manner. The death of the monster Medusa and the death of Nature – embodied by the dead bats and bees – are seen as being synonymous. There is a mournful aspect to this sculpture, as Boyle challenges the viewer to consider the violence enacted both upon women as well as upon the natural world.

Contemporary feminist artists such as Shary Boyle and myself are mining the past, revisiting the universal narratives of mythology and, as Boyle succinctly stated, “propos[ing] some other kinds of stories.” Inspired by the second wave feminists, who coined the phrase the personal is political, we disrupt the problematic, gender-biased narratives of traditional myths by inserting our own personal, idiosyncratic content into the larger framework of these universal stories. This personalized content adopts the symbolic vocabulary of myth and, through creative tactics such as role-playing, re-imagines these stories from contemporary feminist perspectives. Mythological motifs traditionally associated with women – namely the allegorical link made between women and nature – is wielded as a deconstructive weapon that knowingly acknowledges this association while at the same time playfully subverting it. The female subjects that populate our work ache, bleed, bloom and otherwise manifest their interior worlds in a number of strange and wondrously magical ways.