A paper diorama of a Danish shop published on Illustreret Familie Journal (second half of the 1930’s). Discovered this gem on an Italian-language blog. I don’t have any more information on this wonderful piece, but wanted to share it’s gorgeousness.

Art musings and other great profundities

Topics relating to visual art, either mine or someone else’s.

Goth like me; or, why does little Jenny mope in her bedroom all day, wearing black and writing bad poetry?

I have a theory that some people are simply born to be Goth. Long before I knew of such a subculture, I was, by virtue of natural inclination, compelled to seek out the dark, the morbid, and the theatrical. These are the mainstays of ‘the Gothic’, a darkly romantic movement within art, music, fiction and fashion.

My gateway music into all things Goth was The Cure’s 1989 album Disintegration, back in my undergraduate art school days — which is, as far as anyone is concerned, precisely the right place to discover the angst-ridden wails of Robert Smith. Similar bands, such as Bauhaus, Joy Division, and the Sisters of Mercy, soon followed. While I was not then– nor am presently — a daily devotee to dressing exclusively in the Goth style, I have held a continued fascination in all things related to the Goth subculture ever since those early, fateful days of art school.

Fashion is critical for the Goth, with adherence to a particular mode of dress strict, to the point of orthodoxy. There is, as it turns out, not one type of Goth, but several. These include the Classic Goth, the Romantigoth, the Cybergoth, Fetish Goth, Vampire Goth, Glitter (or Perky) Goth, Victorian Goth, Steampunk, Gothabilly, Gothic Lolita, and…well, the list is long, indeed. Below is a brief description of some of my personal favourite modes of Goth dress.

Classic (or Traditional) Goth

Siouxsie Sioux, lead singer of the seminal ’80’s Goth band Siouxsie & the Banshees, and the figurehead for the first generation of Goths.

The Goth subculture evolved from Punk in the early 1980s, with the London club The Batcave ostensibly functioning as its musical and stylistic home base. Famous club regulars included musicians such as Robert Smith, Siouxsie Sioux, Steve Severin, Marc Almond and Nick Cave. Collectively, their dark, moody and often somber music and penchant for theatricality shaped this new subculture, creating its very distinctive look and feel. While Punks were angry anarchists, Goths were melancholic fatalists.

The fashion of the Classic Goth was heavily influenced by British-based Punk. Fishnet, leather, and piercings were prominent, and the colour black was worn, head-to-toe, with slavish devotion. BDSM paraphernalia, such as black leather slave collars, corsets and harnesses, was also common. Hair was very big and very, very teased (it was the ’80s, after all) and make-up was heavy and often exaggerated. Trendsetters like Siouxsie Sioux served as models for the uniform of the Classic Goth female: black, spiky-teased hair, fishnet, leather, studded belts, wristbands and collars, dark, heavy eye make-up and thickly lined, deep red lips.

Victorian Goth

One of the biggest influences on Gothic fashion has been the imagery in Gothic literature and their movie counterparts, particular that of Victorian writers such as Edgar Allen Poe and Bram Stoker. Victorian fashions like corsets, lace, frock coats and pale skin are popular throughout the scene, but maybe none wear them with as much style as the Victorian Goth.

Like their Victorian role models, the Victorian Goths wish to convey an image of decorum and dignity. Clothes must be elegant and, for many, historically accurate. Ball dress and mourning garb are particularly prominent in the scene.

Victorian Goths may also indulge in activities that were popular in Victorian high society, including theatre, masquerades, tea parties and poetry. And, naturally, any kind of Dickensian or other Victorian festival that gives them an excuse to parade around in costume.

As for music, opera and classical are the true Victorian Gothic genres, but Victorian-inspired bands such as Rasputina are also acceptable.

Steampunk

The antiquated, refined elegance of Victorian Goth and a rough, edgy futurism may seem a completely incompatible combination. But, thanks to a particular genre of fantasy, the two have been successfully wedded to create the Steampunk Goth.

Steampunk is, in essence, science fiction that takes place in the low-tech setting of the past — very often the Victorian era. In Steampunk, you may find steam-powered robots, clockwork computers and complex contraptions made from wood, brass and wheels. The merging of Victorian imagery with quirky technology is doubtlessly of huge appeal to many Goths, but perhaps the most important links between Steampunk and Goth culture are the Victorian writers who inspired the genre, including Mary Shelley and Edgar Allen Poe.

Steampunk Goth fashion is highly creative, incorporating elements that evoke Victorian technology such as clocks, keys and cogs. Although Steampunk is not a music scene, acts such as Rasputina, Emilie Autumn and Abney Park have all been cited as having Steampunk appeal.

Gothic Lolita

While largely inspired by the Western Goth movement, the Gothic Lolita is a wholly Japanese creation. Inspired by Visual Kei and cosplay, the Lolita tries to closely emulate a demure, doll-like Victorian girl. Modesty and elegance are critical, and little or no skin should be exposed in Lolita costumes.

The Gothic Lolita is the darker sister of the frothy-pink Sweet Lolita, and typically dresses in a combination of black and white, or entirely in black. Eyes tend to be dark and smoky but, on the whole, make-up tends more towards the natural tones rather than the theatricality of Goth “white face” — which wouldn’t work on Asian skin, anyway.

This style has recently come full circle, with Westerners now borrowing fashion elements from the Japanese. Westernized versions of Lolita fashion tend to minimize the girlish frills and add an element of coquettish sex appeal.

The Gothabilly

What do you get if you mix Elvis Presley, The Cramps, a bunch of old horror movies and a splash of lounge? Bizarrely, you get Gothabilly – a rare and exotic breed of Goth with rather eclectic tastes in both music and wardrobe.

With styles originating from “Rockabilly” (American 1950s rock n roll) and “Psychobilly” (1980s punk with a heavy rockbilly influence), Gothabilly is visually and musically a play on retro, kitsch aesthetics – but with a dark twist. Like Deathrock, which often shows many overlapping traits with Gothabilly, the music and imagery is frequently tongue-in-cheek and deliberately cheesy. As such, many Gothabilly bands sport such creative names as Nacho Knoche & The Hillbilly Zombies, Cult Of The Psychic Fetus, and Vampire Beach Babes.

Gothabillys tend to be some of the brighter Goths out there, with their vivid tattoos, cherry accessories and ubiquitous polka dot clothes.

Cannibals, werewolves and tentacles: The web searches that bring you here.

Blog statistics are a fascinating gateway into the collective unconscious. While the identities of those who’ve visited my blog remain anonymous, their mouse clicks remain on record and provide an insight into the topics that interest them most. What occupies people’s thoughts during those moments of procrastination when they are not writing that report for their boss or essay for that class? Cannibals, apparently. More specifically, Ruggero Deodato’s 1980 horror film Cannibal Holocaust, a film that’s still considered controversial after 32 years and, likely due to its continued notoriety, received the most “hits” on my blog. If they’re not seeking information on cannibal films, people are looking into the Canadian teenage werewolves of Ginger Snaps which, as far as I’m concerned, is a much better use of their time.

Periodically, I will write about topics other than horror films, though these topics are as equally strange and macabre. Heinrich Hoffmann’s darkly comedic children’s book Der Struwwelpeter (1845) has garnered a great deal of interest on my blog, as well as the eroticized anatomical art of Jacques D’Agoty and anatomists of the 18th-century. The mythological vagina dentata and Japanese ‘tentacle erotica’ draw a fair amount of interest, as one might expect.

Celebrities and famous artists predictably top my statistics tally. People have searched on marquee names from art history including Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Odilon Redon, and Hannah Wilke (though the latter is lesser known), as well as contemporary visual artists Loretta Lux, Marcel Dzama and Shary Boyle. And, 45 years after her death, Jayne Mansfield still attracts a large amount of attention. I only wrote about her in a post last week, and she’s #22 on the list of “all-time” top searches. Of course, her story is a ‘perfect storm’ for achieving immortality on the Internet: a beautiful, buxom starlet, who reportedly dabbled in Satanism, died young and in most grisly manner (depending on which account you read, she was either scalped or decapitated in a car accident). We are, as a species, a ghoulish bunch.

Here’s the top 30 searches, according to WordPress:

| cannibal holocaust | 577 |

| ginger snaps | 287 |

| holocaust | 279 |

| struwwelpeter | 253 |

| loretta lux | 247 |

| odilon redon | 246 |

| max ernst | 246 |

| vagina dentata | 184 |

| daguerreotype | 123 |

| tentacle erotica | 109 |

| cannibal | 97 |

| jennifer linton alphabet series | 94 |

| walerian borowczyk | 91 |

| max ernst collage | 84 |

| der struwwelpeter | 78 |

| hannah wilke | 70 |

| contes immoraux | 67 |

| drag me to hell | 56 |

| agoty angel | 49 |

| anatomical art | 46 |

| jayne mansfield | 45 |

| marcel dzama | 43 |

| the descent | 40 |

| macabre art | 37 |

| drag me to hell old lady | 37 |

| best animated movies of all time………… | 33 |

| holocaust pictures | 33 |

| redon | 33 |

| irreversible | 28 |

Now, get back to work…

p.s. One of the funniest web searches I’ve seen to date would be this one: “horror movie with a women who seducing and kill men with her vagina.” Hey, who am I to judge? Incidentally, there is such a film — not surprisingly, it’s Japanese and called Killer Pussy. You’re welcome.

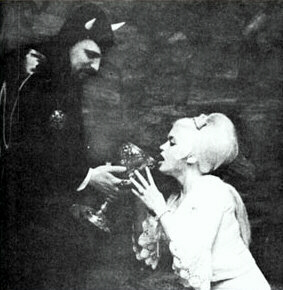

The Devil and Jayne Mansfield.

Photograph of Jayne Mansfield supposedly participating in a Satanic ritual with the creator of the Church of Satan, Anton LaVey. Publicity stunt? Most definitely.

“If you’re going to do something wrong, do it big, because the punishment is the same either way.” — Jayne Mansfield (1933 – 1967).

Long before Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian, there was the original publicity-seeking, trash-talking sex symbol, Jayne Mansfield. Notorious for her openly naughty behaviour and 40D-21-36 physique, the shrewd career woman Mansfield seldom missed an opportunity to dismiss her Hollywood rivals, namely Marilyn Monroe and Mamie Van Doren. Of the media’s constant comparison of Mansfield to her blonde bombshell competitors, she famously remarked: “I don’t know why you people [the press] like to compare me to Marilyn or that girl, what’s her name, Kim Novak. Cleavage, of course, helped me a lot to get where I am. I don’t know how they got there.” Meee-ow, Ms. Mansfield.

Since her gruesome death by car accident in 1967, many legends have emerged around Jayne Mansfield. One of these concern her supposed relationship with Anton LaVey, the American founder of the Church of Satan and author of The Satanic Bible. As with many legends, this one was most assuredly manufactured:

LEGEND: Jayne Mansfield, Hollywood sex symbol and actress, was a card-carrying Satanist and had an affair with Anton LaVey.

REALITY: Publicity agent Tony Kent, an associate of Ed Webber, arranged the meeting between Mansfield and Anton LaVey as a publicity stunt. LaVey was smitten with the actress. Mansfield, who made no secret of her many affairs, denied knowing LaVey intimately, and no associate of hers has ever confirmed any supposed romance. In a 1967 interview she said, “He had fallen in love with me and wanted to join my life with his. It was a laugh.” According to LaVey’s publicist Edward Webber, Mansfield would ridicule her Satanic suitor by calling from her Los Angeles home and seductively teasing him while her friends listened in on the conversation. LaVey’s public claims that he had an affair with Mansfield began only after Mansfield’s death in an automobile accident, which he also claimed was the result of a curse he had placed on her lover Sam Brody.

SOURCES: Edward Webber (interview by Aquino 6/2/91); interview with Mansfield quoted in Jayne Mansfield by May Mann, Pocket Books, 1974.

Satanist or not, I find it difficult not to adore Mansfield’s calculated naughtiness and shameless self-promotion. She knew fully well what the public wanted, and she served them up with a wink and a plunging neckline. I also love the fact that she totally dissed the head of the Church of Satan — talk about having real chutzpah. Here’s Mansfield performing a kooky little “hula dance”, for your viewing pleasure:

Classical mythology revisited: the shrewd ecofeminism of Shary Boyle.

The last (I promise) of the grad school essays I shall inflict upon you. In this one, my task was to compare my work with that of another contemporary visual artist. I chose Shary Boyle. The astute among you will recognize a passage or two from my Master’s thesis in this essay. Hey, it’s not plagarism when you cannibalize your own writing.

Throughout history, visual artists have fleshed out mythological subjects and generated images based on traditional, time-honoured stories. Myths supply an accessible and universal narrative to which the artist can attach a personal story. Renowned scholar and mythologist Joseph Campbell describes one of the goals of myth as “…effecting a reconciliation of the individual consciousness with the universal will.” Similarly, in his essay “The Expressive Fallacy” Hal Foster cites Nietzsche’s discussion of an artist’s use of myth to express an interior world: “The whole notion of an ‘inner experience’ enters our consciousness only after it has found a language that the individual understands – i.e., a translation of a situation into a familiar situation…” The “language” to which Nietzsche refers can be interpreted as “mythology” which provides a universal narrative to which all cultures, no matter how disparate, have access. The “inner experience” may be read as the personal, psychological or emotional world that the artist seeks to materialize through the use of myth. In short, myths connect us to each other by anchoring the idiosyncrasy of the individual to a universally shared point of reference.

In my own art practice, I frequently make use of myths and archetypes as cultural ready-mades into which I insert my own personal history and meanings. Myths are reinterpreted in my work from a feminist perspective that considers gender representation in these mythological narratives. Another contemporary Canadian artist who employs a similar creative, feminist tactic is Shary Boyle. A commonality in our work is the use of female mythological subjects that evoke the traditional, allegorical link between women and nature. Rather than simply offer a critique of the feminized concept of nature, however, both Boyle and myself use motifs derived from nature in a subversive manner that transform our female subjects in strange, fantastic ways. The transformations and mutations that our mythological heroines experience provide the visible, external evidence of their inner psychological and emotional world.

In her work prior to 2008, Boyle’s use of fairytales and mythological subjects tended to be global rather than specific. Her phantasmagoric imagery suggested the realm of dreams and myths without representing a particular legend or cultural tradition. Her two pencil and gouache drawings that we shall examine, both dating from 2003 and simply called Untitled, are evidence of her generalized incorporation of myth. Both drawings involve remarkable incidents in which a single female figure, isolated on the white void of the paper, quietly experiences a magical transformation. In Untitled (fig. 1) we are confronted with a woman in a bright red dress sitting contentedly in the grass, hands resting peacefully in her lap. The drawing is linear and economical; the grass on which the woman sits is minimally drawn. Two long, yellow plant stalks topped with white blossoms grow outwards from the eye sockets of the woman, a strange phenomenon that has not managed to disturb her serenity. The very fact that the woman appears unconcerned by this fantastic event seems to suggest that this transformation is metaphoric as the flowers are a manifestation of an interior psychological state. Equally, the woman may have simply acquiesced to the inevitability of this strange transformation. The subject of Boyle’s second drawing Untitled (fig. 2), a prepubescent girl whose rigid stance and sideways glance suggests that she’s somewhat more alarmed by the tangled bush growing out from her mouth, nevertheless seems to accept the strangeness of this event as normative.

In her essay entitled “Ornamental Impulse”, art writer Josée Drouin-Brisebois comments on Boyle’s surreal transformations as a manifestation of the emotional and psychological worlds of her subjects. “Boyle’s [figures]”, says Drouin-Brisebois, “express the inner life of the emotions materially.” Drouin-Brisebois cites the review of art critic Robin Laurence for Boyle’s paintings Companions (2004), wherein Laurence states: “Boyle’s portraits suggest that what looks outwardly freakish in others is the metaphorical equivalent of inward aspects of all our characteristics and circumstances.” Thus, the plant life that blooms from the bodily orifices of these female subjects is emblematic of their interior states, though what precisely those states would be remain vague and mysterious.

The mythology to which Boyle attaches her idiosyncratic narratives serves to anchor the work in tradition and provide the viewer with visual clues as to how one might interpret her dream-like imagery. For instance, the otherworldly flora of these drawings reference allegorical and mythological associations of women to nature. Rather than challenge the traditional dichotomy of women and nature, Boyle embraces it in a subversive manner. According to Drouin-Brisebois, Boyle’s women “become…nature in unsettling ways – verdancy out of control or a parasite that takes over the body…” Boyle acknowledges the allegorical tradition while at the same time engaging a sinister playfulness that alters it.

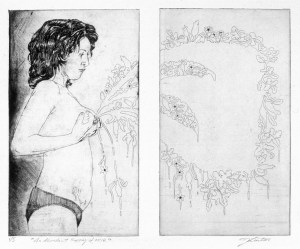

Similar to Boyle, otherworldly flora plays a prominent role in my 2006 intaglio print entitled An Abundant Supply of Milk (fig. 3). Whereas Boyle rarely identifies her female subjects as aspects of herself, my work makes frequent use of self-portraiture and is characterized by an autobiographical content. This particular self-portrait shows myself standing in profile, naked save for a pair of underwear. With my hands I squeeze my breasts and produce an exaggeratedly large spray of breast milk. This cloud-like spray of breast milk, in turn, blossoms into a soggy mass of flowers. Like the drawings of Boyle discussed earlier, this print recognizes the mythic association between women and nature, and in particular the concept of a nurturing “mother nature”, while at the same time subverting it. The nourishing food that is breast milk has transformed into a bizarre floral mass that, rather than natural, appears inexorably alien. Created in the months that followed becoming a first-time mother, this image addressed my response to the strange transformations enacted upon my body as a result of pregnancy and childbirth. The milk-flowers that spring forth from my breasts represent an externalization of the estrangement I felt from my own body.

A second, earlier self-portrait speaks not to a feeling of estrangement but to the human impulse towards creation, both in art as well as in procreation. The coloured pencil drawing entitled Genesis (fig.4) illustrates the growth of a leafy, magenta and orange plant stalk out of my opened mouth. This fanciful stalk terminates in a perfectly round, ripe pomegranate fruit. Similar to the heroines of Boyle’s drawings, my visage appears untroubled by the unconventional growth of this fruit as if this were the result of a natural, internal process. In contrast to Boyle’s 2003 Untitled drawings, however, the magical vegetation of Genesis recalls a very specific mythological story while at the same time evoking the women-nature dichotomy. The appearance of the pomegranate in this drawing is highly significant as it is a direct quotation from an earlier body of work in which I assumed the role of Persephone, a tragic heroine from Greco-Roman mythology. This role-playing allowed for the insertion of personalized content within the larger context of a universal narrative. Or, as Nietzsche expressed, the myth of Persephone provided “…a translation of a situation into a familiar situation.” We will return to this discussion of Persephone after an introduction to Boyle’s latest works, one of which, coincidentally, deals directly with this same myth.

As previously stated, Boyle’s work is frequently characterized by a global adoption of mythology, her imagery an amalgam of different mythic traditions synthesized with her own idiosyncratic symbolism. The recent unveiling of Boyle’s latest porcelain sculptures at the 2008 grand reopening of the Art Gallery of Ontario, however, provides an exciting and atypical exception to this aspect of her work. Boyle was commissioned by the AGO to create work that responded to the gallery’s permanent collection. She selected two 18th-century Italian bronze statuettes by Giovanni Battista Foggini with which to engage in a conversation across history. The subjects of Foggini’s sculptures are two commonly depicted Greco-Roman myths: Perseus slaying Medusa and The Rape of Proserpine. Boyle’s porcelains offer feminist reinterpretations of these myths while simultaneously maintaining her characteristic surreal imagery that hints at the internal, psychological world of her subjects.

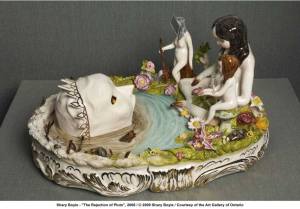

Boyle’s response to Foggini’s The Rape of Proserpine re-imagines the Greco-Roman myth upon which it is based and addresses the violent and sexually problematic subject matter of the original Baroque bronze. Her delicate porcelain sculpture entitled The Rejection of Pluto (fig. 5) casts the titular deity as a hideously yawning monster and not the sinewy, handsome abductor of Foggini’s statuette. In her 2008 interview with art critic Sarah Milroy featured in The Globe and Mail, Boyle discussed the responsibility she felt as a feminist artist in rendering an alternate version of this classical myth: “I guess I just felt that this subject matter had to be engaged. I had been asked inside the museum, and I felt a kind of responsibility to interrupt some of those narratives, to propose some other kinds of stories.”

Proserpine is the Roman goddess of springtime, wife of Pluto and mythological equivalent of the Greek goddess Persephone. Her story is one of great emotional power: an innocent maiden abducted by the lustful god of the Underworld and forced to become his bride. In the Globe and Mail interview, Boyle related the version of this Greco-Roman myth that inspired her reinterpretation:

“…Pluto, the Lord of the Underworld, fell in love with Proserpine, the beautiful daughter of the harvest goddess. Lust incarnate, he emerges from Hades through a pond in the glade of the water nymph Cyane, wreaking havoc on this sacred sylvan spot and seizing Proserpine by force, making her his bride in Hell. Cyane, who protects the natural realms, weeps tears over this loss, so much so that her tears replenish the landscape Pluto has devastated.”

The scene of Boyle’s The Rejection of Pluto is the idyllic glade of the water nymph Cyane, decorated with exotic flowers, seashells and fairytale toadstools. The monstrous head of Pluto emerges from the water, his cavernous mouth yawning open as if to swallow his intended victim. Bright red-orange light, suggestive of the flames of Hell, flickers inside the mouth and eyes of the hollow, chasmal head. The water that immediately surrounds Pluto’s head appears brown and putrid and the vegetation bleached white, all vitality having been drained out by its proximity to the god of the Underworld. The female characters of this story – the girl-child Proserpine, her mother Demeter, and the nymph Cyane – are all gathered in a group at the opposite end of the glade. The amphibious water nymph Cyane glowers fiercely at Pluto, defending Proserpine whom Boyle has cast as a small child wounded by mirrored shards. According to Boyle, these three female figures “represent emotional, mental and physical resistance under siege.”

The crucial role that nature plays in The Rejection of Pluto can be likened to that of Boyle’s 2003 Untitled drawings, although the correlation between women and nature in the sculpture have been further strengthened. The landscape of The Rejection of Pluto reflects the violation suffered by Proserpine through its transformation from lush verdancy to polluted wasteland. This transformation of the landscape symbolizes Proserpine’s psychological and emotional turmoil in much the same manner as the mirrored shards that have pierced her flesh represent her physical violation. Boyle’s shrewd interpretation of the Proserpine/Persephone myth emphasizes the allegorical link between women and nature in her analysis of the mistreatment of both women and nature in the world.

The tragic heroine Persephone has also been depicted as a prepubescent girl in my 2000 mixed-media drawing entitled The Bitter Seed. In this drawing, I combine an image of myself as a child with the myth of Persephone as a means to address the difficult territory of childhood sexual abuse. By adopting the role of the mythological heroine, I translate and universalize my personal experience. Through the use of this metaphor, I strive to make an emotional state palatable and thus more easily approachable by the viewer.

The Bitter Seed takes its name from the pomegranate seed that Persephone was forced to eat, thus sealing her fate as the goddess whose annual death and rebirth would usher in the changing seasons:

“Persephone was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of agriculture. Hades, the lord of the Underworld, surprised Persephone one day while she was picking flowers and carried her off to be his bride. Demeter, the distraught mother, threatens to destroy all mortal men by causing an endless drought unless her daughter is returned. Zeus, who is the king of the gods at Olympus, commands Hermes to fetch Persephone from the realm of Hades. The wise Hades chooses to obey the command of Zeus; however, before Persephone is returned, he tricks her into eating a seed from a pomegranate. This deception is later revealed when Demeter asks her daughter “…have you eaten any food while you were below? If you have not, even though you have been in the company of loathsome Hades, you will live with me and your father…but if you have…you will return again beneath the depths of the earth and live there a third of the year; the other two-thirds of the time you will spend with me…”

To the ancient Greeks, the myth of Demeter and Persephone served to explain the death and regeneration of plant life each year. The metaphoric link between women and nature is quite overt: Persephone personifies the cycle of the seasons through her annual sacrifice.

In The Bitter Seed, my childhood self stands thickly outlined in black against a brightly coloured background reminiscent of a stained-glass window. One of my hands holds aloft a pomegranate, above which hangs the phrase “dirty girl.” I stare quizzically at both the fruit and the phrase, my child mind unable to fully grasp their meaning. Like the pomegranate in the Persephone myth, the fruit I hold represents violation and entrapment. Similar to the girl-child Proserpine in Boyle’s sculpture, who displays her wounded arms for the consideration of the viewer, my child-self in The Bitter Seed holds the pomegranate up as a symbolic manifestation of inner “wounds”.

Fig. 6. Jennifer Linton, "St. Ursula and the Gorgon’s Head", coloured pencil and drawing ink on Mylar, 62 cm x 80 cm, 2002.

The victimization of the girl-child Persephone in The Bitter Seed is later redressed in my 2002 drawing St. Ursula and the Gorgon’s Head (fig. 6) in which I assumed the role of the Catholic Saint Ursula, the patron saint of schoolgirls. In a manner similar to The Bitter Seed, this drawing blended autobiographical elements with mythological role-playing in order to universalize personal experience. The heroine of St. Ursula and the Gorgon’s Head assimilates two divergent mythological traditions: the hagiography of the Catholic saint with the Greco-Roman myth of the Gorgon Medusa. More avenging angel than saint, St. Ursula is shown adorned with angel wings and holding aloft a sword and the severed head of Medusa. The mouth of the snake-haired Medusa gapes open in a silent scream while a magical bloom of red flowers bleed from the wound of the severed neck. In the background, graphic and highly stylized red flowers also appear to bleed. Much like the strange, sinister flowers of Boyle’s 2003 Untitled drawings, these violent blossoms subvert the traditional woman-nature dichotomy and the association of women with a passive and nurturing feminine principle.

Women are frequently cast as the prize at the end of the hero’s quest but are seldom depicted as the active, adventurous hero themselves in mythology. This gender-biased tradition was best summarized by Joseph Campbell in his 1982 interview with Rozanne Zucchet from his collected writings entitled “The Hero’s Journey”:

“I was teaching these courses on mythology and at the end of my last year there this woman comes in and sits down and says, ‘Well, Mr. Campbell, you’ve been talking about the hero. But what about the woman?’ I said, ‘The woman’s the mother of the hero; she’s the goal of the hero’s achieving; she’s the protectress of the hero; she is this, she is that. What more do you want?’ She said, ‘I want to be the hero!’ So I was glad that I was retiring that year and not going to teach any more [audience laughter].”

While Campbell’s anecdote evidently amused his audience, it also underscores the gender discrimination inherent in mythological models. The sword-wielding heroine of St. Ursula and the Gorgon’s Head constitutes my feminist response to Campbell and this gender-biased tradition. My heroine adopts the stance traditionally occupied by the male hero Perseus who, as the Greek myth tells us, beheaded the female monster Medusa. Additionally, the gender of Medusa in my drawing has been switched from female to male as the image of the severed gorgon’s head my heroine holds is, in fact, a direct visual quotation of a painting by Caravaggio where Medusa is uncharacteristically portrayed as male.

The representation of gender also plays a crucial role in Boyle’s second porcelain sculpture commissioned by the Art Gallery of Ontario. Entitled To Colonize the Moon (fig. 7), this sculpture encapsulates her response to Foggini’s bronze statuette Perseus Slaying Medusa as well as to the traditional Greco-Roman myth that she “has interpreted in light of both her environmentalist and feminist ideas.” Boyle’s reinterpretation of the myth views Medusa as a “very misunderstood monster” who suffers a number of indignities and violations resulting from the capricious cruelty of the Olympian gods. The severed head of Medusa lies atop a funeral pyre comprised of dead bats and bees, the expression on her lifeless face one of sad resignation to her tragic fate. In stark contrast to the heroic romanticism of Foggini’s Perseus, Boyle’s version of the Greek hero is a lily-skinned, rosy-cheeked effeminate boy who sits in quiet repose while he wipes the blood from his sword. This traditionally triumphal moment has been undercut by the calmness of the scene and soft, unheroic body of Boyle’s Perseus. The violence of the story is not celebrated, but merely represented in an anticlimactic manner. The death of the monster Medusa and the death of Nature – embodied by the dead bats and bees – are seen as being synonymous. There is a mournful aspect to this sculpture, as Boyle challenges the viewer to consider the violence enacted both upon women as well as upon the natural world.

Contemporary feminist artists such as Shary Boyle and myself are mining the past, revisiting the universal narratives of mythology and, as Boyle succinctly stated, “propos[ing] some other kinds of stories.” Inspired by the second wave feminists, who coined the phrase the personal is political, we disrupt the problematic, gender-biased narratives of traditional myths by inserting our own personal, idiosyncratic content into the larger framework of these universal stories. This personalized content adopts the symbolic vocabulary of myth and, through creative tactics such as role-playing, re-imagines these stories from contemporary feminist perspectives. Mythological motifs traditionally associated with women – namely the allegorical link made between women and nature – is wielded as a deconstructive weapon that knowingly acknowledges this association while at the same time playfully subverting it. The female subjects that populate our work ache, bleed, bloom and otherwise manifest their interior worlds in a number of strange and wondrously magical ways.

Walerian Borowczyk’s “Contes immoraux”: The bloodthirsty Countess meets European softcore cinema.

Walerian Borowczyk (1923-2006) was a Polish filmmaker who was, in the early years of his career, the creator of astounding stop-motion animations. Nightmarish and surreal in nature, animated short films such as Renaissance (1963) and Jeux des anges (1964) brought Borowczyk critical acclaim in the rarefied world of avant-garde filmmaking. Commercial success, however, eluded him until his venture into live-action cinema with his infamous art-house-meets-softcore films of the 1970’s. A consummate provocateur, Borowczyk challenged his audience with Contes immoraux (‘Immoral Tales’, 1974) and La bête (‘The Beast’, 1975) — films which some critics derided as “contentless pornography” due to their wholesale preoccupation with nudity and sexuality. While the charge of “pornography” is not entirely unwarranted, I would maintain that Borowczyk’s meticulously-detailed set design, careful art direction and signature surreal style elevate films such as Contes immoraux from mere “sexploitation” to softcore cinema with considerable artistic merit.

Now, don’t get me wrong — from a straightforward “is this movie good or not?” perspective, Borowczyk’s Contes immoraux is not an especially good film. What dialogue there is — and there’s mercifully little — is completely inane. The action is glacially slow, due in part to a camera that lingers incessantly over the bushy nether regions of naked girls. It is ironic, then, that as a purely softcore film Contes immoraux also falters. By the standards of contemporary pornography, Borowczyk’s film is rather too tame to satisfy current erotic appetites. It’s all breasts, bums and bush, and precious little sex. Thus, we are left with a paradoxical film that is neither artful enough for the art-house, nor raunchy enough to function as pornography.

Film still from "Contes immoraux". Paloma Picasso stars as Erzsébet Báthory, the notorious 15th-century Hungarian countess who allegedly bathed in the blood of young women as a means to preserve her youthful appearance.

What the films of Borowczyk do possess, however, are stunning visuals that perfectly synthesize elements of the erotic with the grotesque. Given his early animations, which were bizarre and nightmarish, it is not at all surprising that Borowczyk would continue his exploration of the grotesque in later work like Contes immoraux and La bête. A primary example of this is the Erzsébet Báthory segment of Contes immoraux, the third and most accomplished segment of his four-part erotic anthology. Set in 1610, this segment stars Paloma Picasso (the daughter of Pablo) in the role of Countess Elizabeth Báthory, the notorious 15th-century Hungarian noblewoman legendary for her cruelty and sadism. Amongst her many reputed atrocities were the infamous ‘bloodbaths’, in which the Countess would soak in her victim’s blood in order to retain her youth and beauty. Borowczyk downplays the savagery of the Báthory legend, and instead offers up a positively demure Countess. The segment opens with the round-up of the nearby village girls by the Countess’s henchmen. The next several minutes are dedicated to extended scenes of the girls bathing and generally frolicking in the shower stalls of the Báthory castle. There’s virtually no dialogue, focusing all of our attention on the sumptuous colour palette and beautifully-composed camera shots. After the frivolity of the showers, the naked girls are lead en masse into a large bedchamber. Elizabeth Báthory reappears, wearing a gossamer white dressing-gown, adorned with lace and pearls. The crowd of girls approach the Countess and stroke her pearl-encrusted gown admiringly. Rapidly, however, the scene transforms from sultry to savage, as the girls begin to violently tear at the dress, ripping it to shreds. They fight amongst each other over the pearls that fall, and the once sexy scene of nubile young girls turns into a bloody, animal rampage.

The scene quickly cuts to a close-up of the bloodbath of the Countess. The white limbs of Paloma Picasso fill the screen as she luxuriates in her bath, twisting back and forth in the frothy red. The heightened aestheticism, with the rich, vibrant red blood against white skin, cleverly undercuts the grotesque/horror aspects of the ‘bloodbath’ and the mass-murder that occurred (off-screen) in the previous scene.

The films of Walerian Borowczyk are not widely available, but cinephiles and film geeks can likely find these in the better “alternative” video stores or at midnight screenings in rep cinemas.

Some girls are more lethal than others: that deadly ‘vagina dentata’ grin.

The wonderful closing shot of an empowered Dawn from Mitchell Lichtenstein's "Teeth." Incidentally, Mitchell is the son of famed American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein.

The vagina dentata is the myth of a woman that possesses a castrating ‘toothed vagina‘. This myth exists across many different cultures and seems to address a global anxiety amongst men over the ‘otherness’ of women’s bodies and sexuality. In the Freudian psychoanalytic model, the vagina dentata is emblematic of castration anxiety amongst very young boys who, upon their awareness of the biological difference between male and female genitalia, develop an unconscious and irrational fear that their own penis will be ‘removed.’ Of course, Freud’s theories have fallen out of favour in therapeutic practice over the past decades, owing to the fact that his views of both women and homosexuality are antiquated and obviously problematic. And yet, the myth of the vagina dentata continues to be pervasive in contemporary culture, albeit in a much more symbolic manner.

Mitchell Lichtenstein’s 2007 horror-comedy film Teeth employs the vagina dentata myth as a mischievously playful plot device. The main character Dawn unknowingly possesses a ‘toothed vagina.’ The reason for her biological abnormality is never explicitly given, although several panning camera shots of a power plant looming in the distance behind Dawn’s house — not to mention the cancer that plagues her sick mother — suggest a mutation due to environmental pollutants. An unfortunate succession of events, including date rape and sexual abuse by a gynaecologist, transform the teenage Dawn from a virginal spokesperson for Christian abstinence to a sexual vigilante who wields her vagina dentata as a weapon of revenge. Although the premise feels a bit weak to carry a feature-length film, there’s still gory-fun to be had as the number of severed body parts predictably rise. Men will find this film squirm-inducing, for obvious reasons. Cross your legs and enjoy.

Kate Kretz. "Vagina Dentata Purse", 2002, hand sewn, hand dyed velvet, wire, thread, shaped shells, purse frame, 10 x 14 x 7".

Related articles

- The art of Hannah Wilke: ‘Feminist Narcissism’ and the reclamation of the erotic body. (jenniferlintonart.wordpress.com)

2010 in review according to the WordPress stats monkeys.

The stats helper monkeys at WordPress.com mulled over how this blog did in 2010, and here’s a high level summary of its overall blog health:

The Blog-Health-o-Meter™ reads Fresher than ever.

Crunchy numbers

A Boeing 747-400 passenger jet can hold 416 passengers. This blog was viewed about 5,600 times in 2010. That’s about 13 full 747s.

In 2010, there were 27 new posts, growing the total archive of this blog to 31 posts. There were 79 pictures uploaded, taking up a total of 17mb. That’s about 2 pictures per week.

The busiest day of the year was December 14th with 104 views. The most popular post that day was Calamari Love: the curious tradition of Japanese ‘tentacle erotica.’.

Where did they come from?

The top referring sites in 2010 were facebook.com, jdlinton.50webs.com, en.wordpress.com, lunettesrouges.blog.lemonde.fr, and search.aol.com.

Some visitors came searching, mostly for cannibal holocaust, loretta lux, struwwelpeter, max ernst, and ginger snaps.

Attractions in 2010

These are the posts and pages that got the most views in 2010.

Calamari Love: the curious tradition of Japanese ‘tentacle erotica.’ December 2010

5 comments and 2 Likes on WordPress.com

Lady Lazarus’s Halloween List: Top 10 Best Horror Films of the 2000s. October 2010

2 comments

Surrealism, alter-egos and private mythologies; conclusion. September 2010

Gallery August 2010

Making art out of dead things, part II: The dioramas of Frederick Ruysch July 2010

1 comment

The art of Hannah Wilke: ‘Feminist Narcissism’ and the reclamation of the erotic body.

I wrote the following essay on American visual artist Hannah Wilke for an art history class in graduate school. I include the full text and images, excluding citations. If you’re a student who discovers this via search engine, then I have every confidence in your research abilities to track down the scholarly sources. Wilke was a seminal Second Wave feminist artist whose work has received renewed interest from scholars since her death in 1993.

The politics of inclusion that shaped feminist discourse in the 1960s and 1970s spawned a legacy of body-based performance art, much of which was associated with women artists who used their own face as a subject of continual exploration. The self- imaging of women artists such as the provocative American artist Hannah Wilke was frequently attacked and dismissed by art critics as being indulgent exercises in narcissism that only served to reinforce the objectification of the female body. The charge of narcissism leveled on Wilke and her work may have been warranted, however, this should not be considered as a pejorative. Rather, the narcissism of Wilke can be viewed as a shrewd feminist tactic of self-objectification aimed at reclaiming the eroticized female body from the exclusive domain of male sexual desire. The ‘self-love’ of narcissism is a necessary component to this reclaiming of the body and the assertion of a female erotic will as being distinct from that of the male artist. Wilke wielded her narcissistic self-love as a powerful tool of critique, defiantly placing her own image into the hallowed halls of the male-dominated art institution.

The term “narcissism” derives from the ancient Greek myth of Narcissus, a beautiful but arrogant youth who cruelly spurned the love of his admirers. For his cruelty, he was cursed by the goddess Nemesis and fell in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. The doomed Narcissus pined away for his unattainable lover – the image of his own self – and literally died as a result of his amorous longing.

Sigmund Freud bestowed the name of this mythic Greek youth upon his psychoanalytic theory of narcissism, a theory that describes normal personality development. According to Freud, the self-love of narcissism is a normal complement to the development of a healthy ego. Whereas a certain amount of narcissism is desirable, an excess of self-love is considered dysfunctional and indicative of pathology. This latter definition of narcissism, the one of pathological self-absorption, has cast our current understanding of narcissism in a negative light and reinforced the use of the term as a pejorative.

The psychoanalytic theories of Freud suggest that negative or pathological narcissism is a specifically female perversion. Art critic Amelia Jones writes that “[d]rawing loosely on Freud’s definitions – which connect narcissism to both a stage of development and to a form of homosexual neurosis – narcissism has come in everyday parlance to mean simply a kind of “self-love” epitomized through woman’s obsession with her own appearance.” Hence, the charges of narcissism leveled on Hannah Wilke were attempts by the critics to summarily dismiss her work as mere manifestations of a woman’s obsessive self-love and infer, according to Jones, that Wilke’s art was not “successfully feminist.”

Critics such as Amelia Jones and Joanna Frueh have championed Wilke and proposed, through their respective writings, a new and positive view of narcissism as a legitimately feminist, subversive tactic in the making of art. In her catalogue essay entitled “Intra-Venus and Hannah Wilke’s Feminist Narcissism”, Jones contextualized Wilke’s work within the framework of her “radical narcissism” and argued that the use of her own image throughout her art is far from the conventional or passively ‘feminine’ depiction of women as seen in advertising and other forms of mass media. Joanna Frueh, in her essay that accompanied the 1989 Wilke retrospective in Missouri, equated Wilke’s “positive narcissism” with a form of feminist self-exploration and an assertion of a female erotic will. Both Frueh and Jones cogently argue for a “positive narcissism” that expunges itself of the negative connotations of Freudian psychoanalytic theory and, in contrast, actively and unapologetically engages in self-love. Wilke enacts an aggressive form of narcissistic self-imaging that defiantly solicits the patriarchal gaze which she then, as Jones writes, “graft[s] onto and into her body/self, taking hold of it and reflecting it back to expose and exacerbate its reciprocity.”

Fig. #1. Hannah Wilke. "S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication". Mixed media (artist's multiple). 1974-75.

Wilke’s active solicitation of the “male gaze” as a method of feminist critique is best exemplified in her photographic series entitled S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication (figs. 1-2), a series which had been originally produced as a box-set artist’s multiple for the 1975 exhibition “Artists Make Toys” at the Clocktower in New York. Wilke commissioned a commercial photographer to capture her semi-nude self-portraits in which she adopts the exaggerated postures of the celebrity and fashion industries. In one such photograph, a sunglass-wearing Wilke clutches her Mickey Mouse toy tight to her partly naked torso as she gazes off-camera at an imaginary paparazzi. She assumed the role of the celebrity art “star” suggested by the witty wordplay of her title S.O.S. Starification Object Series. As with many of Wilke’s titles – for she was fond of linguistic games and frequently engaged in puns – there is a double meaning to be found in the titular pun “starification.” Wilke dotted her own skin with several tiny vaginal sculptures that she had shaped from chewing gum. These small sculptures decorated her body in a manner recalling the practice of ritual scarification employed by certain African cultures as a means of beautification. Given the presence of the vaginal “scars” in combination with the sexy, glamourous black and white photographs of Wilke, it is not difficult to locate the artist’s critical stance on the occasionally painful regimens Western women inflict upon themselves in their conformity to accepted conventions of beauty. Wilke willfully submitted her own body to this ritualized, albeit pretend, self-abuse in order to address this “tyranny of Venus” which, as Susan Brownmiller writes in Femininity, “…a woman feels whenever she criticizes her appearance for not conforming to prevailing erotic standards.” The fact that Wilke herself was, by these same erotic standards, a beautiful and sexually desirable woman does not confuse her aim of critique but rather serves to strengthen her commentary on women’s roles and gender stereotypes. Her overstated, sultry expressions and postures of sexual display invite scrutiny. Wilke was keenly aware of her status as a celebrity art-star as well as a beautiful, eroticized object of desire and she capitalized on both with the S.O.S. Starification Object Series. The original dissemination of this photographic series in a packaged box set, complete with sticks of chewing gum, preformed gum vaginas and phalluses, and the semi-nude artist self- portraits, simultaneously commented on both the artist-celebrity as a commodity as well as the erotic consumption of the female body. Cleverly, Wilke underscored the erotic self-objectification of her image in the extended title for this box set multiple: S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication. We are reminded that this is an adult game, and Wilke’s use of the word mastication in reference to chewing (gum) is likely a pun on masturbation, a suggestion that locates her eroticized self-portraits on the parameters of pornography.

Fig. #2. Hannah Wilke. "S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication". Detail. Mixed media (artist's multiple). 1974-75.

Assimilating the visual language of the objectified female body, Wilke employed her own eroticized body as a metaphorical mirror that she then held up to reflect back the sexual projections of male desire. This act of reflection enabled Wilke to sever her passive (and traditionally female) receptiveness of this male projection and assert her own erotic will. In her collection of essays entitled Erotic Faculties, Joanna Freuh used the phrase “autoerotic autonomy” in reference to Wilke’s images and suggested that her “…self-exhibition may demonstrate the positive narcissism – self- love – that masculinist eros has all but erased.” The empty vessel that is the celebrity or the fashion model – devoid of a personal will as she functions as a receptacle for our projected desires – has been adopted and systematically absorbed by Wilke’s exaggerated poses. For her part, Wilke then engaged her narcissistic self-love as a means to fill these empty vessels with her aggressive sexuality. The sites of female erotic pleasure, namely the mouth and the vagina, are conjured in her chewing gum sculptures while, at the same moment, they hint at the violent aggression of the folkloric vagina dentata.

The consciously sexualized self-objectification of Wilke and the use of her own body as a “professional currency” often elicited harsh criticism from the ranks of feminism, an ideology to which she actively subscribed. Lucy Lippard, the champion of 1970s feminist art, famously wrote that Wilke’s “confusion of her roles as beautiful woman and artist, as flirt and feminist, has resulted at times in politically ambiguous manifestations that have exposed her to criticism on a personal as well as on an artistic level.” Art critics Judith Barry and Sandy Flitterman dismiss Wilke’s self-portraits: “In objectifying herself as she does, in assuming the conventions associated with a stripper, …Wilke…does not make her own position clear…It seems her work ends up by reinforcing what it intends to subvert…” The tense political climate and rapid social change of America during the decades of the 1960s and 70s fueled a radical activism amongst Second Wave feminists. The urgency felt by these activists to affect social change in relation to gender equality frequently generated a feminism that was fervent, even orthodox, in its ideology. This strict orthodoxy was shaped by anti- essentialism – a philosophical stance that rejected the representation of the female body as it was believed too imbued with a history of objectification by male artists – and therefore unable and unwilling to accommodate the sexualized body-based art of Hannah Wilke. The negative reception of Wilke by critics like Lippard, Barry and Flitterman may have been prompted by an adherence to this strict orthodoxy. The complex and ambiguous views of the body and female sexuality that Wilke presented, at times even contradictory to the aims of feminism, generated rancor in this inflexible climate of anti-essentialism.

In her 1978 interview “Artist Hannah Wilke Talks with Ernst” the artist unapologetically spoke of the “ethics of ambiguity” that characterized both her work and life. She addressed, in her honest and unmediated manner, the conflicted views of a woman who, though conscious of feminism, still felt concerned with her appearance and desirability to men. Rather than deny this impulse, Wilke embraced her feminine narcissism and brandished it as a weapon. Such a bold act of defiance and deliberate provocation against the anti-essentialist feminism that dominated the 1960s and 70s later established Wilke as the “…spiritual parent to postfeminist artists such as Tracey Emin…” and anticipated the self-imaging of Janine Antoni and Cindy Sherman.

Wilke was not the only woman artist of her generation to use her own body in a consciously sexualized manner, nor was she the only artist to engage with narcissism as a feminist tactic. Carolee Schneeman’s canonical 1965 Fuses (fig. 3), a film that included photographic footage of the artist having sex with her then-partner James Tenny, was greeted with outrage from the feminist audience who, as film theorist Shana MacDonald writes, “…[were] uncertain how to incorporate the sexualized, erotic and self-produced image provided by Schneemann” Similar to the harsh criticisms leveled on the photographs of Wilke, the erotic self-portraiture of Schneemann’s Fuses was frequently attacked as being “obscene and narcissistic.” According to MacDonald, it was her sexually graphic imagery – imagery that feminist theorists found indistinguishable from the objectified female image being resisted – that caused Schneemann to be misunderstood by her peers and ultimately marginalized.

As the coquettish semi-nudes of Wilke’s S.O.S. Starification Object Series made reference to imagery generated for pornographic use, so too does Schneemann’s Fuses address pornography in order to critique its traditional objectification of women. The repeated, non-linear narrative of Fuses interrupts the pornographic convention that the film necessarily terminate in the obligatory “cum shot” of male ejaculation. The sexuality communicated by Schneemann’s film is highly subjective and anchored in the banal reality of the everyday, including shots of the artist’s cat and the domestic surroundings of her home. The subjectivity of Fuses was further heightened by the literal mark of the artist, evidenced in Schneemann’s use of hand-processing techniques such as collage, painting and scratching directly onto the celluloid. Her infusion of a personal subjectivity performed as a feminist resistance against the sexual- objectification of the female body as seen in conventional pornography. By simultaneously inhabiting the roles of both the image and the image-maker, she positioned herself “not as sex object, but as willed and erotic subject, commanding her own image.” Schneemann’s urge to see her own sexualized image is a manifestation of self-love and the hypothesized “positive narcissism” of Jones and Freuh. As Narcissus romantically yearned for his own image, Schneemann desires to view her own erotic image, not reflected in a pool of water, but projected larger-than-life on the theatre screen. This act is a bold assertion of her narcissism and erotic will.

At first glance Wilke’s S.O.S. Starification Object Series, much like Schneemann’s Fuses, appeared to reinforce the visual language of the objectified female body. The sultry eyes, seductively parted lips and naked breasts of Wilke read as cultural signifiers of female sexual invitation and availability. Lippard may have been correct in her observation that Wilke played both the “feminist and flirt” but her assessment that this polarity stemmed from her confusion over these two roles was essentially wrong. Wilke’s narcissistic self-imaging was not, as Elizabeth Hess charged, an impulse to “…wallow in cultural obsessions with the female body,” but a pointed feminist critique of these same obsessions. In contrast to fashion models and pin-up girls, who passively offer their flesh to be inscribed by male desire, Wilke interrupted this erotic exchange by the presence of her chewing gum “scar” sculptures. Recalling the artistic intervention of Schneemann’s hand-processing techniques in Fuses, Wilke’s sculptures mark the otherwise unblemished surface of her skin and disrupt the easy consumption of her body as an erotic object. She declared the canvas of her skin as the terrain of her own erotic expression, and marked it accordingly. Whereas the youth Narcissus failed to possess his own beloved self-image, Schneemann and Wilke are too shrewd in the deployment of their narcissism to suffer this same fate.

Women artists of the late 1960s and 1970s, such as Schneemann and Wilke, often engaged in the feminist project of reclaiming the female body from previous male privilege. Centuries of depiction by exclusively male artists had rendered the female nude a dehumanized, neutral object. Wilke and her feminist contemporaries sought to rectify this situation by seizing creative control over one’s own body. Performative works such as Wilke’s 1974 Gestures (fig. 4) – a video that featured the artist sculpting her flesh – enact this reclamation by proposing the artist’s own body as an artistic medium.

The thirty-minute black-and-white video Gestures showcases Wilke, her head and shoulders tightly framed, performing a series of repeated, often exaggerated gestures and facial expressions. These gestures are often absurd and comical in nature, while others verge on sexual seduction. A silent Wilke gently pulls and kneads her own face, manipulating her youthful, elastic skin much like the soft, putty-like material of her chewing gum sculptures. Saundra Goldman observed that Gestures “…signaled [Wilke’s] transition from sculpture to performance,” and there is a cyclical component to this transition: the soft, pliable chewing gum that Wilke employed to approximate flesh was now being mimicked by the artist’s own skin.

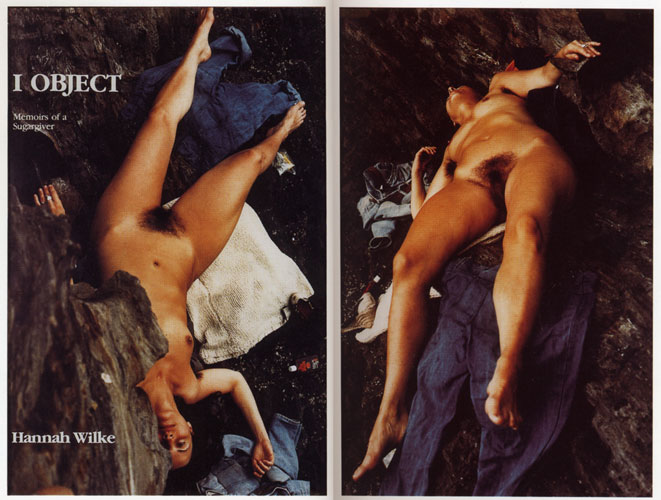

The reclamation of the female body from the privileged control by male artists was the primary motivation behind Wilke’s photographic diptych entitled I OBJECT: Memoirs of a Sugargiver (fig. 5). Wilke’s strong objection was directly aimed at the father of the avant-garde, Marcel Duchamp. While the box set of S.O.S. Starification Object Series offered a critical view of consumerism, the fashion industry and pornography, and Gestures a declaration of control over one’s own body, the faux book jacket of I OBJECT was a direct response to Duchamp’s static rape victim of his infamous diorama Etant donnès (fig. 6). In her 1988 conversation with Joanna Freuh, Wilke stated: “I find Etant donnès repulsive, which is perhaps its message. She has a distorted vagina.” The pun contained in the title I OBJECT, with the play on the word “object” as both noun and verb, laid the foundation for the critical feminist dialogue Wilke embarked upon with this heavy-weight of art history.

The sculptural diorama Etant donnès confronts the viewer with a rustic wooden door, riddled with small holes. A light source shines through these holes, enticing the viewer to peek through and witness a scene hitherto concealed. A pastoral, natural landscape is suddenly revealed, in the foreground of which an alarmingly pale, naked female torso lies inert amongst a bramble of dried twigs and leaves. Her legs are splayed open to reveal her strangely misshapen vagina. The exposed nakedness of the woman, her corpse-like stillness and her derelict location amongst the bramble imply violation and victimhood. As if in a final gesture of violence, Duchamp has chosen to frame the woman’s image within the peepholes of the door in such a manner as to visually decapitate her. The mechanism of display – namely the peepholes through which the scene is revealed – forces the viewer to assume the role of voyeur, further compounding the violation of the woman.

Wilke’s I OBJECT functions as both homage and a critical response to Duchamp: she believed that “to honor Duchamp is to oppose him.” Taken while on a family vacation in Spain, the glossy colour photographs of Wilke show the artist, fully nude, lying atop some discarded clothing on a large, craggy rock. One of the photographs that comprise this diptych approximates the pose of Duchamp’s female torso, with Wilke’s body foreshortened in the camera lens so that her pubic region dominates the picture plane. In stark contrast to the deathly paleness of the woman in Etant donnès, Wilke appears whole-limbed, healthy and tanned. The clothing upon which she lies may have been voluntarily shed in a moment of spontaneous sexual activity, or simply in the act of sunbathing. A bottle of suntan lotion that lies nearby seems to support the latter. The second photograph of the diptych shows Wilke staring upwards at the camera, and directly at the viewer, her face partly concealed by a rocky outcropping. A small but satisfied smile adorns her face. The superimposed text reads “I OBJECT: Memoirs of a Sugargiver” across the upper left portion of the image and then “Hannah Wilke” on the lower left, in close juxtaposition to her smiling face. The presence of her written name paired with her direct, outward gaze reads like a radical declaration of personhood, as if to say I am Hannah Wilke, and here is my body. The feminist gesture of “positive narcissism” comes strongly into play in this particular context. Wilke’s feminist response to the faceless victim of Etant donnès is a bold affirmation of both her personhood and her female sexuality.

As previously mentioned, the close association of women to narcissism partly derives from a loose interpretation of Freudian theory that linked a “woman’s obsession with her own appearance” with a form of psychoanalytic pathology. This association is highly relevant in the critical reception of a work of art; a crucial factor to consider is the gender of the artist. Lucy Lippard, the same art critic who, ironically, dismissed Wilke for being a “feminist and flirt”, denounced the gender divide that existed between the reception of body-based performance work created by male artists against similar work produced by women. “She is a narcissist,” Lippard wrote of women artists, “and Vito Acconci with his less romantic image and pimply back, is an artist.” The crucial distinction between the narcissism of Vito Acconci and Hannah Wilke – for as Rosalind Krauss effectively argues in her essay “Video: the Aesthetics of Narcissism”, Acconci was most assuredly a narcissist – lies in the feminist agenda that fuelled the narcissism of Wilke.

Vito Acconci’s performance-based work often contains ambiguous narratives that frequently wander into the territory of the absurd and contradictory. Much like his contemporary Hannah Wilke, Acconci primarily used his own body as an artistic medium. In his 1972 video entitled Undertone (fig. 7), Acconci is as conspicuously aware of performing as Wilke was of posing in her multitudinous self-images. Undertone begins with Acconci seating himself at a table, the opposite end of which extends in the direction of the camera. This arrangement immediately implicates the camera/viewer into the scene. Acconci closes his eyes, placing his hands on his thighs, and repeatedly mumbles an awkwardly confessional sexual fantasy involving an imagined woman who lurks beneath the table: I want to believe there’s a girl here under the table…who’s resting her hands on my knees…she’s resting her forearms on my thighs…slowly, slowly rubbing my thighs… After several repetitions of this fantasy, Acconci suddenly pauses, straightens his body and stares directly out at the camera/viewer. His hands, now resting on the table top, are clasped together in a pleading gesture while he repeatedly intones: I need you to be sitting there…facing me…because I have to have someone to talk to…so I know there’s someone there to address this to… Acconci proceeds to again close his eyes and place his hands beneath the table. Resuming his mumbled confession, he contradicts his original narrative by stating: I want to believe there’s no one under the table…I want to believe…it’s me that’s rubbing my thighs… The video concludes with a final plea to the viewer to witness the revelation of his fantasy.

Comparable to the revealing titles of Wilke, the layered meanings behind Acconci’s title Undertone provides an important clue to its interpretation. The Concise Oxford Dictionary defines the word undertone as an “underlying quality; undercurrent of feeling.” The underlying theme of Acconci’s video is not found in his repeated sexual fantasy of the imaginary woman under the table – a fiction that his monologue later negates – but rather in his urgent plea directed at the viewer. Acconci compels the viewer to witness his confessional fantasy and thus, by acting in this capacity, participate. A necessary reciprocity exists between Acconci’s performance and the viewer’s reception of this fictitious fantasy. A fruitful comparison can be drawn between Acconci’s Undertone and Wilke’s Gestures video. The performance of Acconci is validated by an exchange with the viewer in the same manner as the poses of Wilke require an onlooker. Equally, both artists achieve a form of sexual power through their performative actions. The crucial difference lies in gender. Even as the awkward disclosure of the fantasy ostensibly renders him vulnerable, Acconci nonetheless seizes sexual control. He punctuates the revelation of his fantasy by a vigorous and masturbatory rubbing of his own thighs, a gesture that creates an uncomfortable tension in the viewer who has been manoeuvred into the place of the voyeur. His repeated pleas to the viewer to witness recall the dynamic of the sexual exhibitionist who requires an onlooker to fulfill his perversion. Acconci enacts his narcissism by forcing his passive-aggressive sexuality upon the viewer.

In the video Gestures, Wilke systematically performs the postures of female display. She seductively rubs her finger across her upper lip. With the practiced smile of a fashion model, she repeatedly tosses her long hair in simulation of a shampoo commercial. Isolated from their usual context of seduction or advertising, these gestures appear absurd – which is entirely Wilke’s point. By repeatedly and methodically performing these gestures, she empties them of meaning. As a young, desirable woman Wilke understands that sexual display is the currency of her power. As a feminist, she acknowledges that these same gestures reduce her to a mere sex object. There is an implicit solicitation of the viewer to witness Wilke’s repetitive actions in much the same manner as Acconci’s Undertone requests participation with his narrative. Their respective sexual power – Wilke as the female sex object and Acconci as the male sexual exhibitionist – require the gaze of the viewer to activate this power exchange.

The deliberate self-objectification of Hannah Wilke seems, in the context of contemporary art practice, very prescient indeed. A consummate agitator and provocateur, her legacy of complex and eroticized body-based art anticipated the work of numerous future women artists whose creative point-of-departure was their own visage. While her work may have been devalued by feminist critics of her generation, a renewed interest from the ranks of feminist scholarship has emerged since her untimely death from lymphoma in 1993. Wilke and her feminist colleague Carolee Schneemann, who worked similarly with erotic self-portraiture, shrewdly engaged with the self-love of positive narcissism to reclaim the erotic female body from the objectification of the male gaze. Fully comfortable within her own skin and embracing all of her very human contradictions – as an artist, a feminist and a woman – she skillfully commanded her own image, both in front of and behind the camera.