Political-phantasmagoria in the art of Marcel Dzama.

The following text is a very short paper I wrote in grad school on the art of Marcel Dzama. Although the ‘voice’ is rather more academic than the writing style of this blog, I thought this paper would be of interest to those amongst you who are not as familiar with this Canadian visual artist. For you researchers out there, I’ve included the citations in a comment at the end of the post.

Marcel Dzama.

Marcel Dzama burst upon the international art world in 1997, mere months after his graduation from art studies at the University of Manitoba. The sinister whimsy of his virtuosic drawings, populated by his now familiar characters of bats, tree-creatures, naked women and anthropomorphic bears, immediately caught the attention of curators and collectors alike. Dzama was one of the founding members of the artist collective the Royal Art Lodge in Winnipeg, the city of his birth. Along with fellow members Neil Farber, Drue Langlois and several other Winnipeg-based artists, Dzama engaged in collective drawing and other types of communal art-making practices. The art production at the Royal Art Lodge placed an emphasis on work that was hand-crafted, recycled, low-budget and characterized by a child-like naiveté. The drawings that Dzama created at this time (1996) already possessed his signature palette of sepia-brown, olive and dark, plum-red and depicted elusive narratives involving cowboys, aliens and strange, sexualized animals. His meteoric rise to fame followed an inclusion of his drawings in 1997 at Plug-In Gallery in Winnipeg and at Richard Heller Gallery in Santa Monica, California 1. Due to the fact that Dzama and several other members of the Royal Art Lodge have established international careers, the collective has since disbanded. Following a major retrospective of the Royal Art Lodge that toured from 2003-05, he moved to New York in 2004, where he presently lives and works 2.

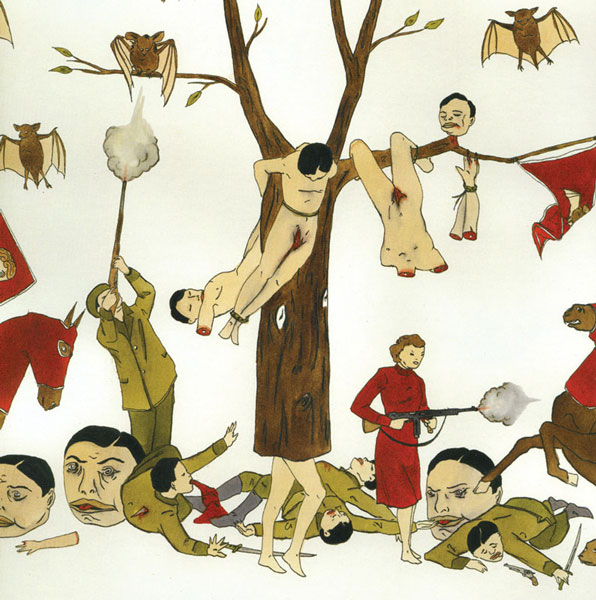

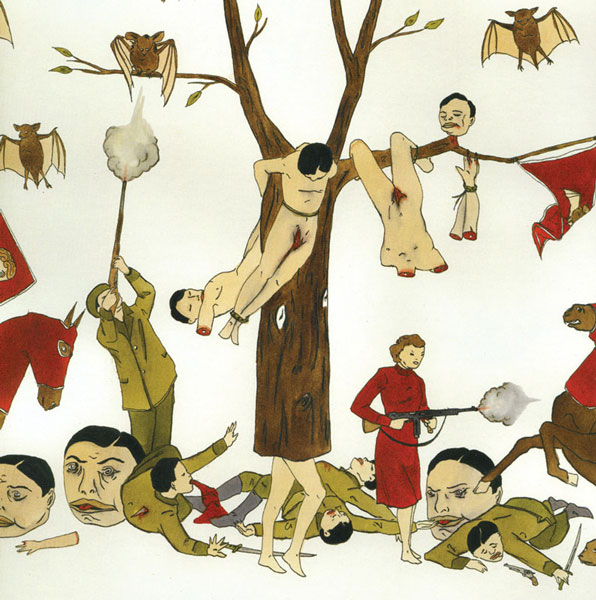

Marcel Dzama. World gone wrong (detail), ink and watercolour on paper, 2005

Dzama’s oeuvre is characterized by frequent references to art history, particularly the work of James Ensor, Francisco Goya and the silent films of the German Expressionists, as well as to imagery based in popular culture like vintage children’s books, fairytales and science fiction. His work blends playful naiveté with violent, psychosexual imagery. The narratives contained in his past work are often resolutely impenetrable to any specific reading by the viewer. However, his 2006 exhibition at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, U.K., seemed to hint at an underlying political subtext in his more recent work 3. This new, political aspect to his work became more solidified in his 2008 dioramas exhibited at David Zwirner Gallery, New York 4.

Given the current geopolitical climate, it is tempting to read Dzama’s recent groupings of mysterious, nostalgic yet timeless soldiers as political art. In his epic 2005 drawing World gone wrong we encounter a scene of monumental violence. As with most of Dzama’s work, the story conveyed by the image is rarely, if ever, straightforward. The bodies of dead or dying soldiers hang from trees or lie at the feet of their pitiless vanquishers. These flag-toting vanquishers are shown either firing guns or, in the case of one enigmatic grouping of soldiers, playing musical instruments in a scene reminiscent of WWII Nazi concentration camps where the best musicians amongst the prisoners were forced to play in macabre orchestras 6. Whether these musicians in World gone wrong number amongst the vanquishers or the vanquished remains unclear. Meanwhile, giant disembodied heads lay grimacing on the ground while bats and red birds swoop overhead.

In World gone wrong we find an example of a very specific quotation from Francisco Goya’s series of etchings entitled Disasters of War (Los desastres de la Guerra).

Francisco Goya, The Disasters of War Plate 39, “Great Deeds Against the Dead”, aquatint and etching, 1810.

The grouping of naked, bound and dismembered male bodies that hang from the tree in the centre of Dzama’s drawing are directly borrowed from Plate 39 Great deeds! Against the dead! in Goya’s horrific pictorial account of the Napoleonic Wars in his native Spain 7. It is tantalizingly suggestive of a political subtext that Dzama’s drawing should quote from the ardently political, anti-war images of Goya. Furthermore, Dzama’s collection of historically uniformed soldiers depicted in World gone wrong, holding aloft strange red flags emblazoned with bats and manically grinning heads, seem to recall the fervent propaganda and costumed ceremony of the Nuremberg Rally and other such emblems of Europe’s fascistic past. In his 2006 interview with Carter Foster for an exhibition catalogue from Ikon Gallery (Birmingham, U.K.) entitled Tree with Roots, Dzama explains the appearance and evolution of these curious bat flags:

“…I was drawing the bat on a flag as a reference to the false patriotism that everyone was calling on recently. Villain-like characters would be doing something evil in the name of this bat flag…but of course it translated into something else at some point.”8

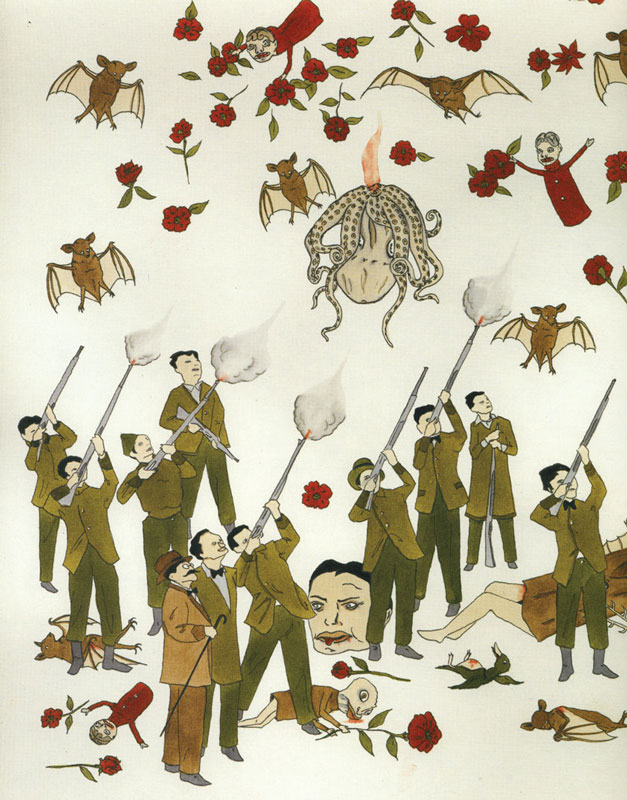

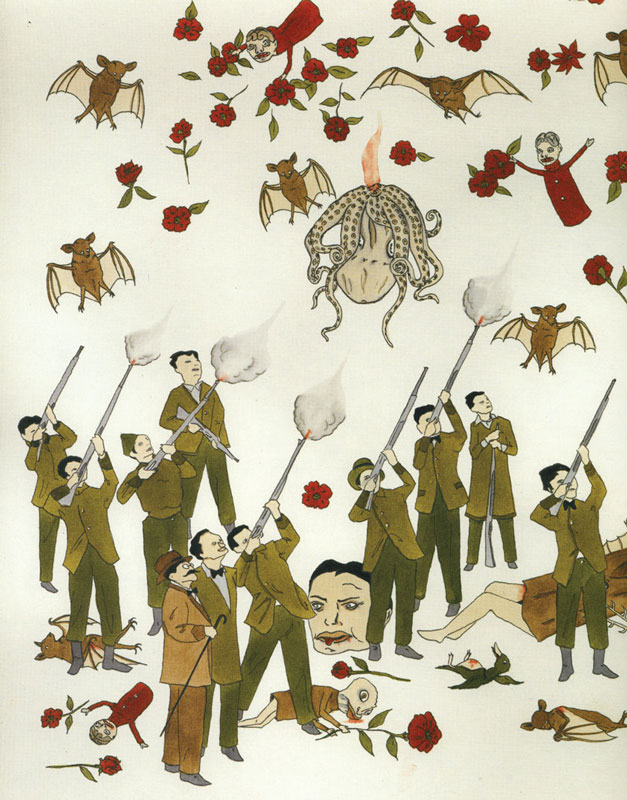

Marcel Dzama, You gotta make room for the new ones (detail), ink and watercolour on paper, 2005.

In the 2005 drawing You gotta make room for the new ones, Dzama offers a surrealistic tableaux of rifled huntsmen and soldiers firing upon a sky raining with bats, flowers, puppets and one octopus10. The dream-like scene seems to defy any attempt at a specific meaning. Dzama provides some clues, however, as to how the viewer might read his narrative. The historic clothing of the huntsmen and soldiers recall the period of time in the 1930’s when the world experienced a surging tide of political fascism and propaganda. Additionally, the red, poppy-like flowers that rain down upon the strange hunting party are reminiscent of the shiny, plastic poppies that adorn coat lapels in Canada on Remembrance Day.

These shiny, red poppies appear even more evident in Dzama’s 2008 sculptural diorama entitled On the banks of the Red River, a monumental work directly modeled after his earlier drawing You gotta make room for the new ones. The shiny glaze on the ceramic sculptures imbue the red flowers with an artificial sheen that even more strongly suggests the plastic Remembrance Day poppies. Dzama’s dense grouping of huntsmen uniformly stand, like a military phalanx, as they point their rifles upwards at the assorted quarry. The unified stance of the huntsmen more closely recall the deadly precision of an infantry than the casualness of a hunting expedition.

In his recent article in Canadian Art magazine entitled “The Haunting: Marcel Dzama’s traumatic fantasy worlds”, art writer Joseph R. Wolin comments on the presence of a political subtext in You gotta make room for the new ones:

“The nearly identical appearances of the gentlemanly sportsmen suggest that we should identify them as if the scene were a political cartoon or a rather anachronistic allegory – the forces of industrial capitalism, militaristic mechanization or masculine colonialism.”12.

Marcel Dzama , On the banks of the Red River (detail), diorama: wood, glazed ceramic sculptures, metal, fabric, 1.79 x 6.35 x 2.18 m, 2008

Wolin concludes his article on Dzama with the comment: “…by making reference to geopolitics with the ingenuous characters that inhabit a world of his own making, he grounds his work [in the] present tense.” Thus, Marcel Dzama has maintained his signature phantasmagoric imagery in recent work but has applied a political reading that feels very topical with regards to current geopolitics. This political subtext serves to ground his highly idiosyncratic work in the real world and provides the viewer with a small foothold on his otherwise strange, mysterious narratives.

43.652500

-79.381667