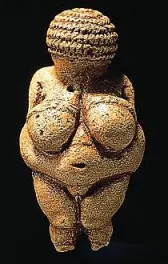

The prehistoric figurine famously known as the “Venus of Willendorf”, which was made between 24,000 and 22,000 BCE.

That flowers-and-Hallmark-card festival of “why don’t you call more often?” guilt we so lovingly refer to as Mother’s Day has just passed, so I thought it topical to dedicate a post to mother archetypes. It goes without saying that, as long as there’s been people, there’s been mothers. Some of the earliest known artifacts of human prehistory are — or, at least, are believed to be — representations of female fertility and motherhood. The most famous of these is the Venus of Willendorf, a small, carved stone figurine of an ancient woman with what could be best described as fleshy, Rubenesque proportions. The exaggerated sexual characteristics of the figurine — her large, pendulous breasts, full, rounded belly and pronounced vulva — seem to support the theory that the Venus was used as a sacred fetish object relating to fertility, perhaps in some sort of Mother Goddess worship. Of course, the true purpose of the artifact remains a mystery:

Like many prehistoric artifacts, the cultural meaning of these figures may never be known. Archaeologists speculate, however, that they may be emblems of security and success, fertility icons, pornographic imagery, or even direct representations of a mother goddess or various local goddesses. — from Wikipedia.

Regardless of the cultural meaning behind such representations of womanhood, various historians and scholars have looked to the prehistoric Venus figurines for images of mother goddesses. The Jungian psychologist Erich Neumann argued that these figurines served as evidence of ancient matriarchal religion in his book The Great Mother: an Analysis of the Archetype (1955), although his theories have since been disputed by subsequent generations of academics. Whether or not there actually was a prehistoric practice of Mother Goddess worship, what we are left with from Neumann’s book is the potent archetypal image of the Great Mother. According to Jungian psychoanalysis, the Great Mother archetype symbolizes creativity, birth, fertility, sexual union and nurturing. She is a creative force not only for life, but also for art and ideas.

But, for every positive, creative force, there must be an opposing, destructive one. This notion is doubly true in the esoteric world of Carl Jung, where all archetypes must, by necessity, possess a shadow self. The dark twin sister of the Great Mother is the Terrible Mother, a force of death and destruction. This archetype inhabits the world of the primordial instincts, and is frequently represented as sub-human or even animal-like in form. A good example of the Terrible Mother archetype is the black-skinned Hindu goddess Kali. Her eyes are described as red with absolute rage, her hair disheveled, and small fangs sometimes protrude out of her mouth. She is often shown naked or just wearing a skirt made of human arms and a garland of human heads. Kali is often accompanied by serpents and a jackal while standing on a seemingly dead Shiva, her male consort. Her open, fanged mouth — with tongue lolling out — is a common characteristic of the Terrible Mother, whose image often emphasizes the oral and is closely related to the mythology of the vagina dentata. Erich Neumann relays one such myth in which “a fish inhabits the vagina of the Terrible Mother; the hero is the man who overcomes the Terrible Mother, breaks the teeth out of her vagina, and so makes her into a woman.” (The Great Mother. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 168.).

Well, in either case — Great or Terrible — I sincerely hope you called your mother this past weekend.